Overview

In order to understand the daily lives of sexual and gender minorities in Bangladesh, the International Republican Institute (IRI) conducted eight focus group discussions (FGDs) and an online survey with Bangladesh’s LGBTI (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex) community.1 This report documents, in their own words, the challenges facing LGBTI people in Bangladesh, challenges that include institutional discrimination, bullying, alienation, depression and physical and sexual violence. This research is part of IRI’s work to promote the inclusion of historically marginalized communities in political discussion and policy decision-making in Bangladesh. In-depth research on community needs is essential for evidence-based policy advocacy.

Background

Gender diversity and sexual orientation are complex and often taboo topics in Bangladesh. On the one hand, a subculture of transgender women and intersex people called “Hijras” have a prominent and widely accepted cultural role in Bangladesh and other South Asian countries. Hijras are born male or intersex but identify as female and dress in traditionally female clothing. For centuries in South Asia, Hijras have performed positive rituals in society: providing blessings to newborn children or holding ceremonies for prosperity or health. Although this cultural tradition has slowly receded in Bangladesh, Hijras/transgender women remain the most widely accepted LGBTI group. In 2013, the Bangladesh government officially recognized a “third gender” category for Hijras, which was codified in 2014. In 2018, the government created an option for “third gender” on voter lists. In 2019, several Hijras competed for spots on the ruling party’s candidate list for women’s reserved seats. Although none received a seat, their candidacies were generally accepted. The status of Hijras is unique in Bangladesh’s LGBTI community. While Hijras can openly express their identity, other sexual and gender minorities cannot. In Bangladesh’s conservative and religious society, non-normative sexual orientations are widely considered unacceptable. Same-sex intercourse is prohibited in Bangladesh under Section 377 of its penal code, which punishes “carnal intercourse against the order of nature with any man, woman or animal” with a maximum punishment of life imprisonment.2

Sexual Identities Unique to Bangladesh/South Asia

- Hijras are born male or intersex but identify as female or nonbinary. Hijras are a gender-based community with specific customs and practices. They hold a culturally unique position in Bangladesh and South Asia through which they confer luck, wealth or good health to others.

- Kothi is a self-identified label that refers to effeminate men.

This provision was first promulgated under British colonial rule in 1860, but has remained in effect. Although Section 377 is not commonly enforced, it has been used to arrest or harass mostly gay and bisexual men. Hijras avoid punishment under Article 377 because of a widely held misunderstanding about their sexual identity. In official government discourse and the public’s common perception, Hijras are intersex—not transgender. Because intersex is not a sexual orientation—intersex people are widely viewed as asexual in Bangladesh—they are not considered “controversial.”

Given the sensitivity surrounding sexual and gender identity in Bangladesh, the LGBTI community is difficult to study. LGBTI people often hide their identity out of fear. This makes conducting rigorous focus group studies difficult and representative surveys almost impossible. Consequently, there is little research that systematically explores the experiences and opinions of LGBTI people in Bangladesh.3 However, the small extant literature points to a common finding: Bangladesh’s LGBTI community faces myriad challenges and often lives in fear.

In 2015, the Netherlands-based human-rights group Global Human Rights Defence partnered with Boys of Bangladesh, which was a gay-rights group based in Bangladesh,4 to conduct a qualitative assessment of the needs and challenges facing LGBT people in Bangladesh.5 Based on 50 interviews with LGBT activists and community members, the report concludes, “The social and cultural resistance against the acceptance of diverse sexual orientations and gender identities leads to an atmosphere of fear, exclusion and stigma for the LGBT community.”

The report contends that LGBT people are “not considered as equal citizens of Bangladesh” and face “institutionalized discrimination in access to justice and public spaces.” In interviews with the researchers, LGBT people said they faced violence, harassment and bullying; feared the police; had low self-esteem and could not freely express their sexual identity.

The same year, Boys of Bangladesh partnered with Roopbaan, which was an LGBT-focused magazine and platform in Bangladesh, to conduct a survey of lesbians, bisexuals and gay men in Bangladesh.6 Although the 571-person survey was non-random (it relied on a network of LGB activists and individuals known to the survey’s enumerators), it was the first large survey of gay men, lesbians and bisexuals ever conducted in Bangladesh. The survey found that a majority (54 percent) live in fear that others will find out about their sexual orientation; over 40 percent face mental stress due to their sexuality; 41 percent reported discrimination, with classmates and friends being the most common perpetrators; bullying, blackmail, physical assault and sexual violence are common; and a majority (60 percent) have never sought legal assistance for crimes committed against them.

Methodology

Building on this research, IRI conducted a mixed-method study of Bangladesh’s LGBTI community that combined FGDs with an online survey.

Focus Group Discussions

In February and March 2020, IRI partnered with a Dhaka-based nongovernmental organization (NGO) that specializes in LGBTI issues to hold FGDs with sexual and gender minorities. The FGDs included 76 participants across eight groups: gay men; lesbians; bisexual men; intersex; transgender men; transgender women/Hijra; queer/nonbinary men and women; and mixed youth (kothi, queer, gender-fluid, gay and bisexual).7 IRI’s NGO partner recruited participants from its network of activists and citizens in the LGBTI community. Each group had between eight and 12 participants, who were of mixed ages (with the exception of the “mixed youth” group) and came from areas across Bangladesh. Participants from outside Dhaka were flown to Dhaka for the FGDs. Each FGD was moderated by a professional FGD moderator with facilitators from the local NGO.

Online Survey

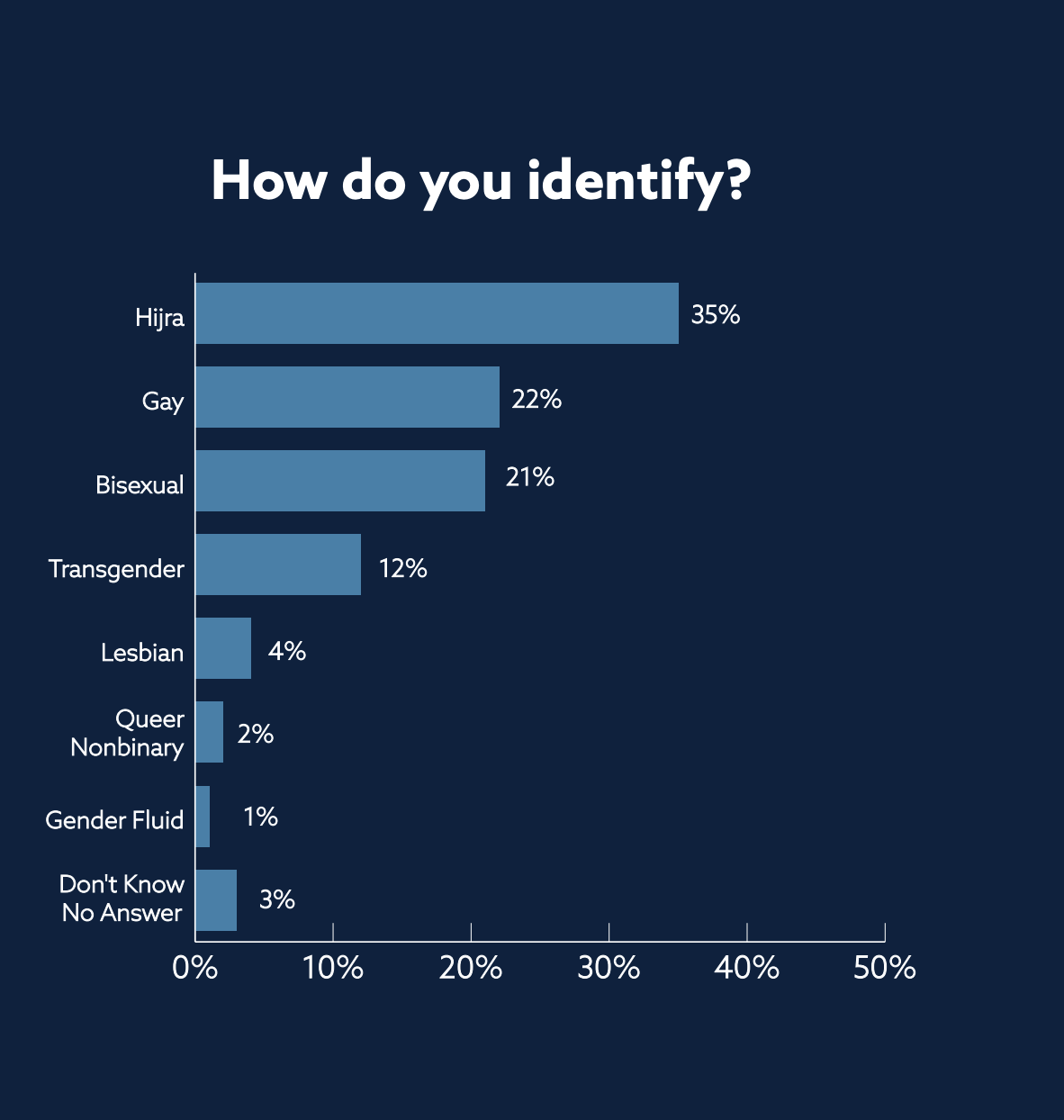

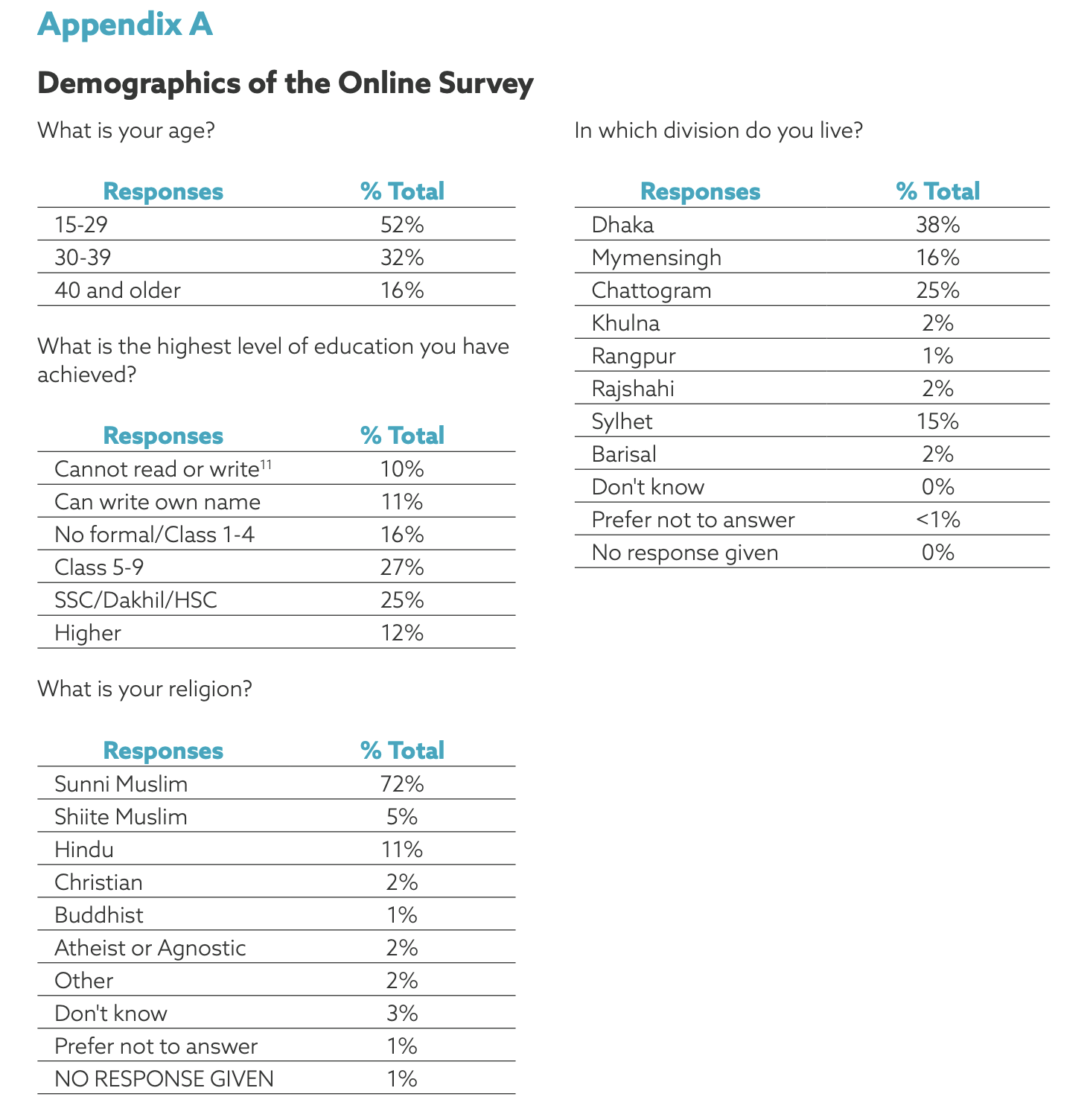

To enhance the reach of the data collection, IRI created an anonymous online survey using the web-based survey tool Survey Gizmo. The survey included 16 questions that explored the LGBTI community’s economic condition, relationship with family and daily challenges. The survey was distributed through a snowball sample using IRI’s local NGO partner.8 The survey was emailed to LGBTI activists and non-active LGBTI people in the NGO’s network (including FGD participants) who were asked to complete the survey and forward it to other LGBTI persons. To ensure participation of illiterate LGBTI people and those who lack access to a smartphone or computer, some respondents were provided a paper copy of the survey (which was then recorded online by a researcher) or received help inputting their responses electronically from community members. Between February and June 2020, 579 respondents completed the questionnaire, which makes it the largest published survey of Bangladesh’s LGBTI community. The respondents were mostly young (52 percent were 29 or younger) and skewed toward lower education attainment (36 percent completed a secondary school certificate at 10th grade or above, while 64 percent did not). Seventy-nine percent were Muslim, 11 percent were Hindu and the rest held other religions or beliefs. And 78 percent of the sample came from Dhaka, Mymensingh, and Chittagong. (See Appendix A for the full demographics of the survey.) Hijra, gay men and bisexual men comprised 78 percent of the sample.

Limitations

The tools employed in this research have limitations. The FGDs included a small sample of individuals and therefore do not necessarily reflect all LGBTI people’s opinions. In addition, the use of an online survey and a snowball sampling approach limits the representativeness of the finding; the sample is non-random and fraudulent online responses are possible. IRI’s Center for Insights in Survey Research (CISR) conducted a data quality check, which identified and eliminated survey responses that appeared duplicative.

For both the FGDs and online survey, the reliance on LGBTI activists, NGO staff and their personal networks skewed the sample of research participants toward urban, educated, young and partially or fully “out” LGBTI individuals. While this is the largest published public-opinion study of Bangladesh’s LGBTI community, it still under-represents the voices of rural and closeted LGBTI individuals. Therefore, the opinions and experiences expressed in this study are suggestive — not representative — of broader dynamics in Bangladesh’s LGBTI community.

The length of time the survey was open could have affected the results. During the five-month period the survey was open, external events could have shaped some respondents’ perceptions of their lives. Although there were no notable events impacting the LGBTI community specifically during this period, it is plausible that changes in current events during the survey period affected responses. In addition, the coronavirus pandemic began approximately two months into survey data collection. The economic, social and mental stress of the pandemic could have affected survey respondents in unique ways.

FGD and Survey Findings

Finding 1: The internet plays an important role in affirming LGBTI identities, which are often understood early in life.

Across FGDs, most participants recognized their sexual identity early in life, but some struggled to accept their sexual orientation. A transgender woman said, “I am like this by birth. I cannot change myself.”9 Another transgender woman said, “In my childhood I thought that God made a mistake when He created me. That’s why I am partly male and partly female. I thought that when I would be an adult, I would become a total female. This is what I used to think.”

Others articulated their sexual identity in religious terms. A man who identifies as gender fluid said, “My creator has created me with His creativity. So, my desires are also created by Him … So if He feels satisfied by creating me like this, I’ll also make myself satisfied through leading this lifestyle.” A bisexual man said, “No parents can give birth to gay or lesbian intentionally, right? So if you want to ask this question, you should ask it to the creator. Only He knows why I am the way I am. Births and deaths lie in His hand.”

For many participants, the internet provided an affirming community that they lacked in their daily lives as young people. A transgender man said, “I used to study on Wikipedia about my community. From there I discovered that I am a transgender.” A bisexual man said, “I used to think I’m the only one like this on earth. I understood my mistake when I started using social media.” A lesbian explained, “I liked girls since my childhood. But Facebook helped me get clearer about this.” Yet these virtual communities often do not lessen the pain of hiding one’s identity in real life. “You will feel very low, when you know your true sexuality, but you can’t reveal it to anyone,” explained a lesbian participant. “Does anybody want to hide their own identity? That’s what we have to do.”

Finding 2: Many LGBTI people face rejection or violence from their families.

While a small number of FGD participants came out to their families and have been embraced, most participants have suffered physical abuse, rejection and ridicule from their families or feared their family’s reaction if they came out. A lesbian explained, “My biggest fear is about my family. If they ever know, they will not let me enter the house. My family is a big thing to me — where I was born, where my siblings are and parents stay. I can’t leave them.”

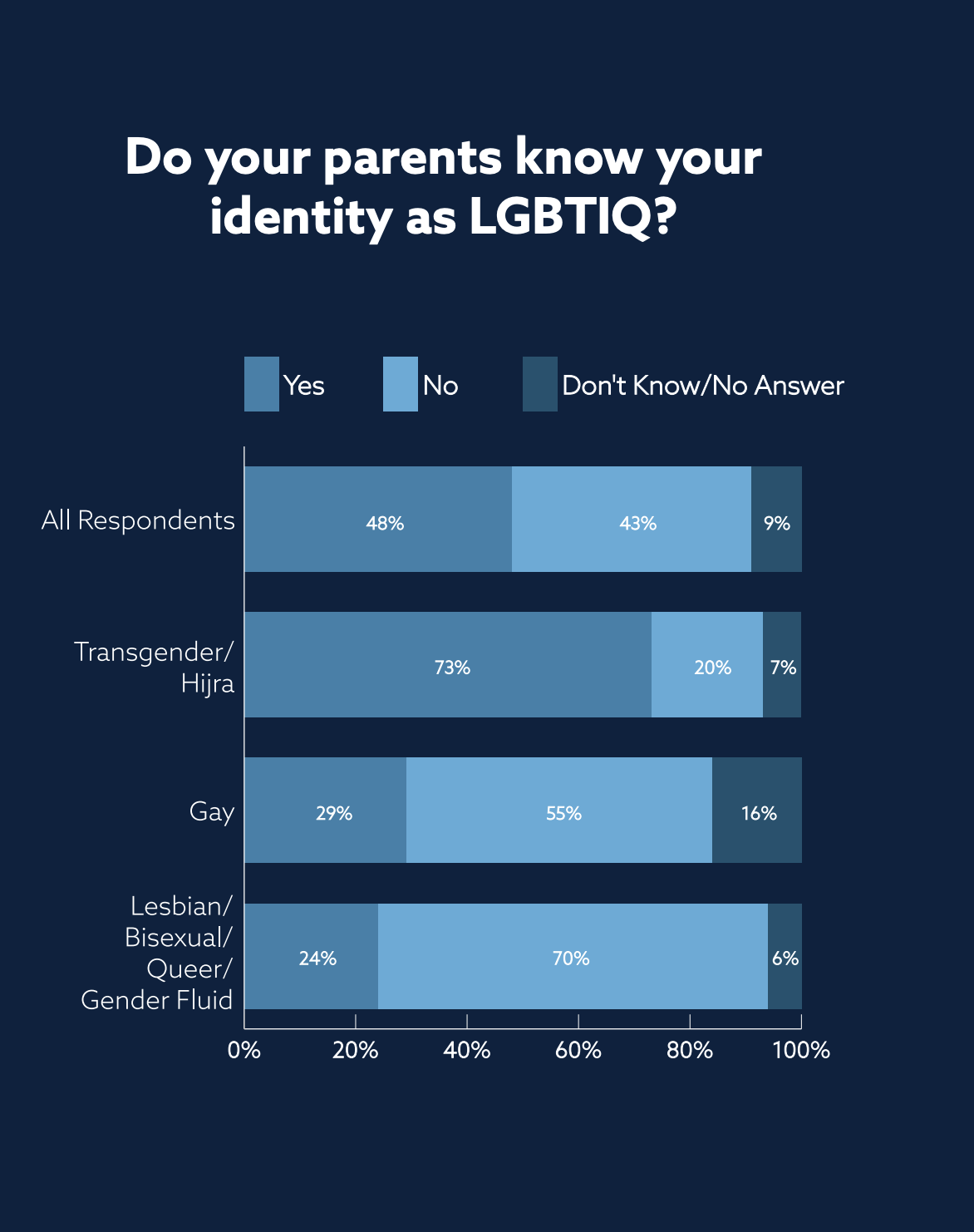

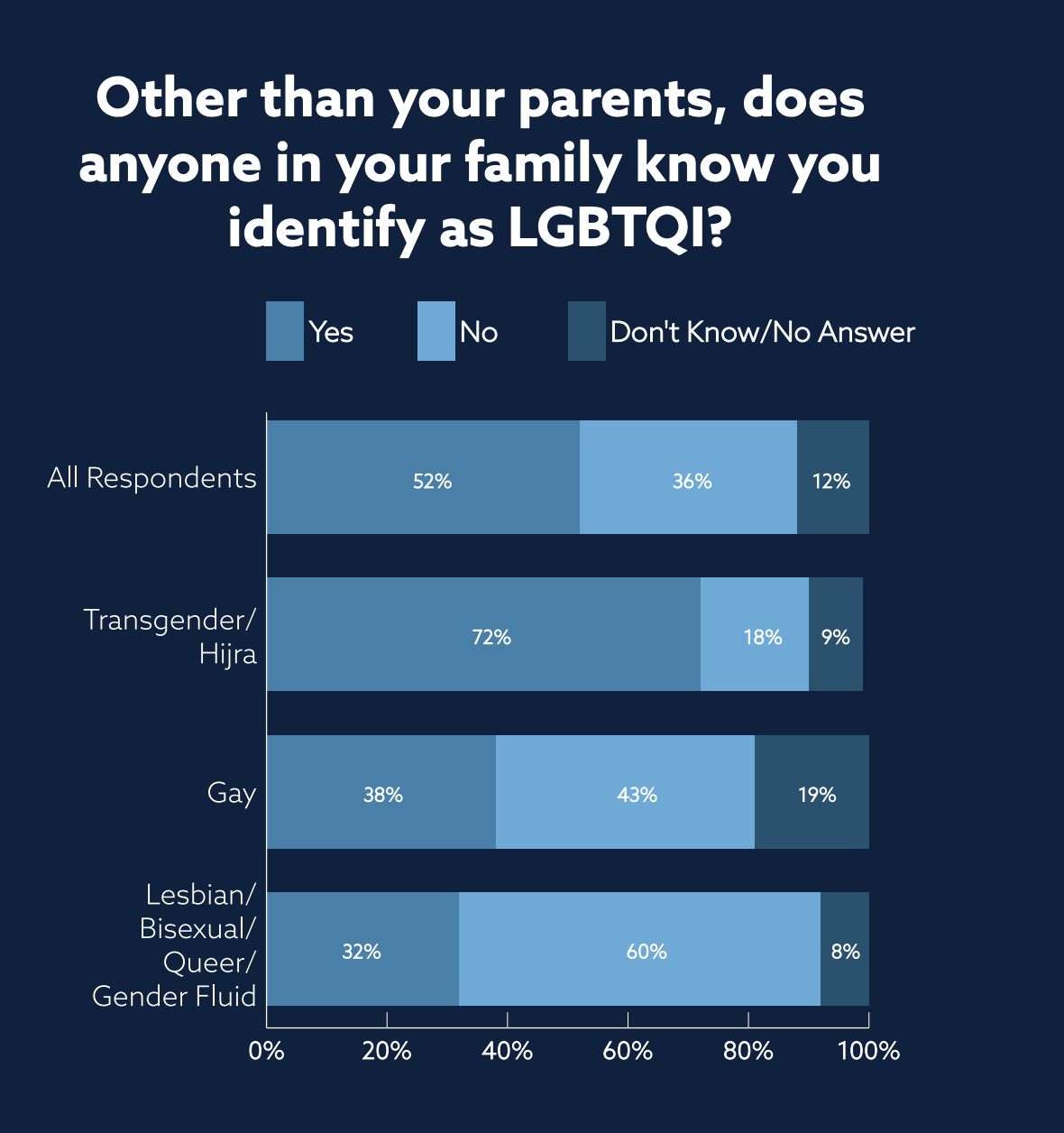

In the survey, 48 percent of respondents said their parents knew their sexual identity, while 43 percent said their parents were unaware. However, these data were different between identity categories. Among gay men and lesbians/bisexuals/queer/ gender-fluid respondents, 29 percent and 24 percent, respectively, said their parents knew their sexual identity, while 73 percent of transgender and Hijra participants said their parents knew their identity. A slight majority of respondents said members of their family other than their parents knew their sexual identity (52 percent).

Many FGD participants have faced bullying and emotional torment from their families. A transgender man said that after he ran away with a woman, his father said, “I do not recognize this girl as my daughter anymore. And what you will do is none of my concern.” An intersex person explained that when their mother was told that a circumcision was impossible, “then my mother got angry and gave me a ladies’ scarf and asked me to commit suicide by that. She told me she doesn’t want a son like me.”

Other participants endured violence. A bisexual man said, “When we used to be home alone, my sisters always helped me do makeup. They also used to allow me to wear their clothes. But one day my father saw me wearing their clothes and beat me up badly.” Another bisexual man said, “If my parents knew [my sexual orientation], they will either commit suicide or they will kill me.” A transgender man said, “To get rid of [my sexual orientation], my father hit me so much that I had a problem with my spine. I am still suffering from this problem. At one point, when he saw that beating wasn’t working, he sent money to my younger uncle to tie me with chains. My father and younger uncle tortured me greatly. They used to beat me so much so that I could get rid of [my sexual orientation].” A transgender woman said her father “beat me, cursed me, scolded me, and ordered me to live properly or leave.”

Other parents insist on marriage or prayer. A gay man explained, “At one point, my family will try to get me married by force. Marriage is a massive torment. I will have to spend every night with a person of the opposite sex whereas I can’t even accept her as a life partner.” A bisexual man said, “My mother used to wake me up at dawn every day and used to ask me to pray. And she also used to ask me to read the Quran.”

Many closeted participants anticipate being kicked out of their family homes and are therefore building their savings first. “When my career will develop and studies will be over, maybe I will inform them then,” explained a gay man. “If I inform them before that, they might throw me out of the house. So, I would need a place to live. I don’t have such a place for me now.”

The intersection of religiosity and family honor forced many participants into a tenuous agreement with their families to hide their sexual or gender orientation in public. A gay man said, “My elder sister has indicated to me that if I don’t tell anything about myself at home, she will still accept my decision to not get married.” He continued: “So, my case is an open secret. They know but I will not openly admit anything. If I want to live single, then they have no objection with it.” Another gay man said, “My family insists that I do things within the four walls and whatever I do that should not harm my family’s reputation.” An intersex person whose father is a politician explained, “If they think of me as a problem for their reputation and political planning, it won’t take a minute for them to kill me. That’s why they used to hide me as much they could.” A bisexual man concluded, “I actually think that respect is a very big thing and it’s going to be totally ruined if I tell it to my family. I’d never want my family to get disrespected for my faults. Because I know that I’m at fault here since our society doesn’t like these things.”

Because of these challenges, many participants are closer to their friends than their families. “It has become apparent that my friends know about my life more than my family,” said a gay man. “They know about my complications and what’s going on in my life. To me, my friends are my family.”

Finding 3: Many LGBTI people have severe mental-health challenges.

Across the FGDs, participants from different sexual orientations described intense feelings of anguish, depression and suicidal tendencies because of familial and social isolation.

Feelings of depression were particularly common among intersex participants, whose lack of a single sexual identity caused heightened feelings of alienation. “I can hardly sleep at night. Different kinds of thoughts pop up in my mind,” said an intersex participant. “I think what will I do if I get older? I have no children, no husband, no family.” Another intersex participant explained, “I am neither a boy nor a girl. The doctor told me that I am a boy. I used to go to the bathroom to check if I am a boy. For the last 10 years I have stopped doing that because I don’t like looking at myself when I don’t know what I am … Our birth is a sin for a lifetime.”

An intersex participant described their pain at seeing their parents suffer. “One day I asked my father to pray for me, so that I can die first among his six children. My parents are tense about me and cry for me … Later my father said, ‘If I can kick you and bury you, then I’ll get peace.’ Then I thought … Are you not happy that I am alive? Will you be happy if I die? … Let’s see if I can die as I want to make you happy.”

One day, I told my mother everything. I always used to think that when I will reach the age of marriage, I will flee my house or commit suicide.

Gay Man

Transgenders suffer from excessive depression and it takes time for them to settle in life.

Transgender Woman

After a breakup, I became more isolated. I was in depression. Suicidal feelings continued to work on my mind.

Transgender Man

Many lives are being wasted. Many people commit suicide at one stage. Some are being accepted by their families. Most of them are not. Many people have to marry despite their unwillingness.

Lesbian

When I was about to get married, I felt like I was dead. I lost all motivation to stay alive.

Bisexual Man

Finding 4: Bangladesh’s conservative society creates an unaccepting environment for LGBTI people.

The vast majority of FGD participants said Bangladeshi society does not accept the LGBTI community. An intersex person said, “According to our society the relationship between a boy and a girl is valid … Here the relationship between two boys will never be accepted.” A lesbian noted, “From home to state to society, we are accepted nowhere.” A transgender woman said, “Our parents don’t tell us to leave. It is the society that is doing everything. We can’t study because of the society. When we wear the clothes of men, the society calls us Hijra. When we wear the clothes of women, the society calls us Hijra. Then what will we do? Assemble us in one place and kill us all by brushfire. I can’t see any other option.”

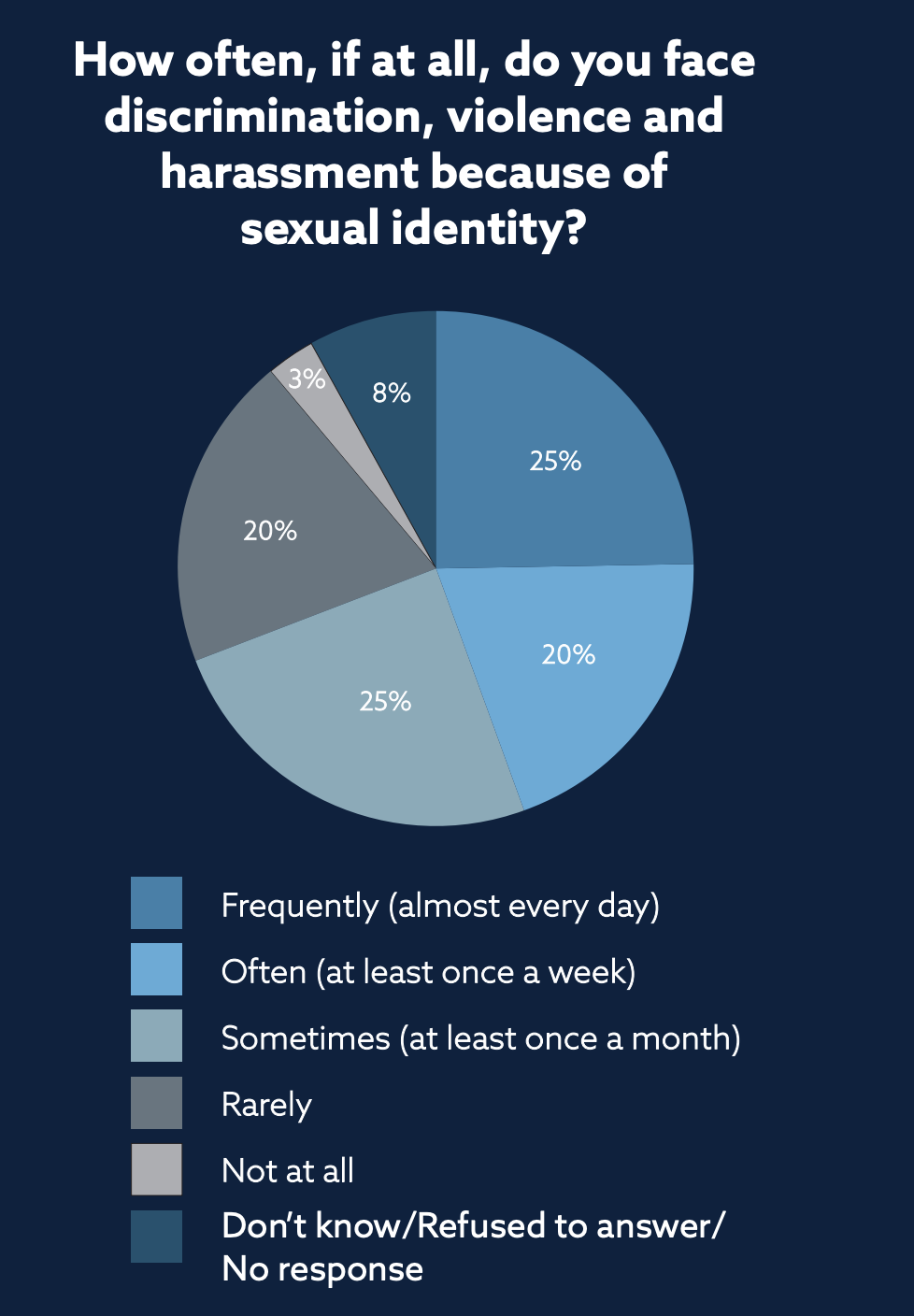

In the survey, over 50 percent of respondents said they faced discrimination, physical violence, mental torture, verbal harassment and sexual harassment. Other commonly cited challenges included social stigma, bullying, sexual violence, threats, stalking and extortion. Forty-five percent of respondents said they faced “discrimination, violence or harassment” almost every day or at least once a week. Transgender and Hijra respondents reported the most frequent discrimination.

Social intolerance toward LGBTI people can result in threats of violence. A man who identifies as queer said, “Some of the comments that I heard from general people was ‘killing these people is the only solution.’ They pass comments like shooting or butchering these people will take them to paradise.” Online, where LGTBI people can express themselves honestly under the cover of anonymity, participants said pro-LGBTI blogs or Facebook posts are inundated with threats and negative comments.

The participants said religion feeds this intolerance. “In the context of Bangladesh, people are blindfolded by Islamic thoughts,” said a gay man. “They don’t want to accept homosexuality in any way. And normally, the families also don’t accept it.” Several participants noted that Islamic preachers promote rejection of and violence toward the LGBTI community. Yet one participant said the problem lies with society: “People use religion as an excuse to express their personal views. They are using religion,” said a gay man.

In response to intolerance in the name of religion, many participants used religious rejoinders. A transgender woman asked, “Man is a creation of God. If that is so, then who created me? Who created my soul?” A bisexual man explained, “If a religious leader comes … we’d want him to treat us like other humans. We were created from the same Creator … Thus, he should accept us … We’re living on the same earth. They shouldn’t throw us away from society.”

Other participants maintained personal religiosity despite the intolerance they face. A gay man said, “Practicing your own religion and having different sexuality are different things. I’m gay. That doesn’t mean I don’t have any religion or that I’d talk bad about religion … My sexual practice is one thing and my religious view is another thing.” An intersex person said, “There is no rule that you have to be an atheist or have to have hatred toward God if you are LGBTIQA. My belief in God has nothing to do with LGBTIQA. I belong to a religious family. Personally, I am religious. I like to say my prayers.” A bisexual man argued that religious intolerance was pushing away otherwise devout Muslims: “As a matter of fact, people who talk or walk in a different way, they end up stopping going to mosque because people mentally torture them. I had to stop going to the mosque.”

Other participants noted the double standard applied to the LGBTI community. “Ninety percent of our country are Muslims, so they won’t ever accept it,” said a bisexual man. “But on the other hand, Muslim-Hindu-Buddhist, everyone is going to hotels with their girlfriend or boyfriend but no one says anything about it. Religion says that’s unlawful, yet people don’t talk much about this. But whenever homosexual people do it, they burn us or kill us.”

Finding 5: Physical and sexual abuse is common among LGBTI people, particularly for gay men, bisexual men, and transgender women.

Stories of sexual abuse and sexual harassment were particularly frequent in the FGDs among gay men, bisexual men and transgender women. There is a pervasive sense of insecurity among these groups. “I am insecure with my family, society, religion and nation. It means I am insecure everywhere,” said a gay man.

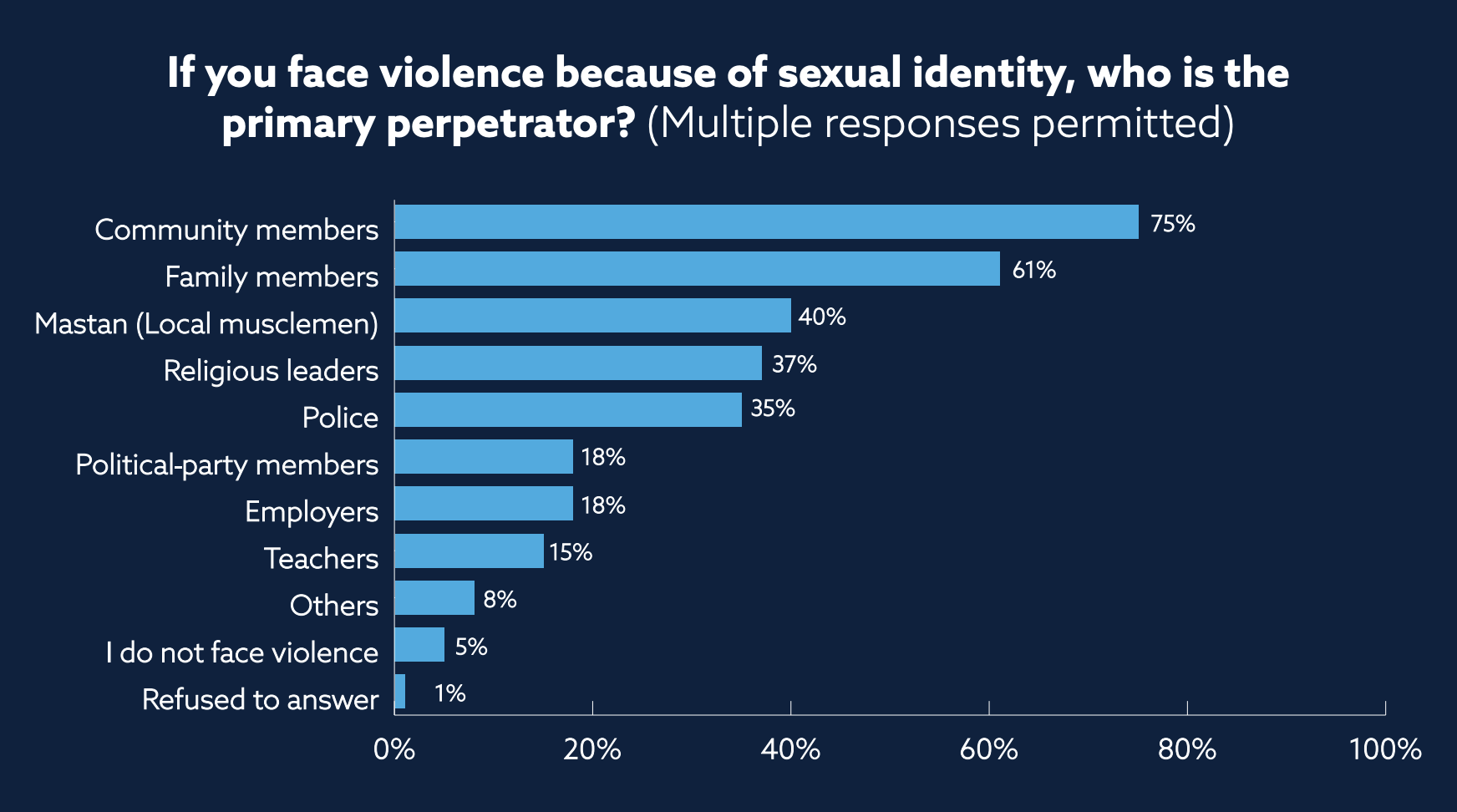

In the survey, respondents said the primary perpetrators of violence against LGBTI people were neighbors in their community (75 percent), family members (61 percent), local criminals (40 percent), religious leaders (37 percent) and police (35 percent). Other answers included political-party members, employers, colleagues, teachers, doctors and classmates.

Many participants said assault and harassment are common. A gay man alleged, “Violence occurs more in the gay community. Each and every night, somebody gets raped. I call this ‘legal rape’ in the context of Bangladesh.” A transgender woman said, “In our society, every man and boy has a strong negative perception about us. They think that transgender means free sex service. For this reason, we get sexually harassed every now and then.”

Several participants discussed being raped as children. A transgender woman said, “From the time I was in grade 2–3 [age 7–8], I was forced into sex by many people.” Several gay men described assault or harassment from neighbors, instructors and taxi drivers. Another transgender woman explained, “When I was very young and studying in grade 5 [age 10], I got raped for the first time. For the next 1–1.5 months, I was always bleeding in the washroom. I couldn’t tell anyone anything … If I ever murder someone, it will be these three men. This is my dream.” A transgender woman said abuse is also common in schools and families: “It happens in school life too. It also happens with teachers and in the family. It happens between two relatives. They get this opportunity more than others … I am talking about relatives like paternal and maternal uncles.”

Gay and bisexual men are also victims of extortion schemes. Several participants described being lured to an isolated location under the guise of a relationship, only to be assaulted and blackmailed. A gay man described that after meeting a group of men, “they took me to a nearby flat and tortured me … They … threatened that they will reveal everything about me to my family. I requested them not to do that. They demanded money from me.” Another gay man said, “This is not an isolated incident. There are many more. This kind of incident is occurring on university campuses regularly.” He described an incident in which his friend was raped by four “political men” who then demanded 40,000 Taka [470 USD] to not reveal his sexual identity.

Because of the taboo around homosexuality, LGBTI people have few options for help. A gay man who suffered an assault said, “I don’t have anyone with whom I can share these things. At that time, I had recently been separated from my family. I was in a financial crisis. I couldn’t do anything.” A bisexual man told the story of his friend who was violently raped and beaten and in need of medical attention. When he arrived home, his parents left him to die: “No one took him to hospital; he died there. They didn’t go because his father was chairman [a local political position] and it would ruin his reputation.”

Finding 6: In the public sector, private sector and media, LGBTI people often encounter ignorance, discrimination and humiliation.

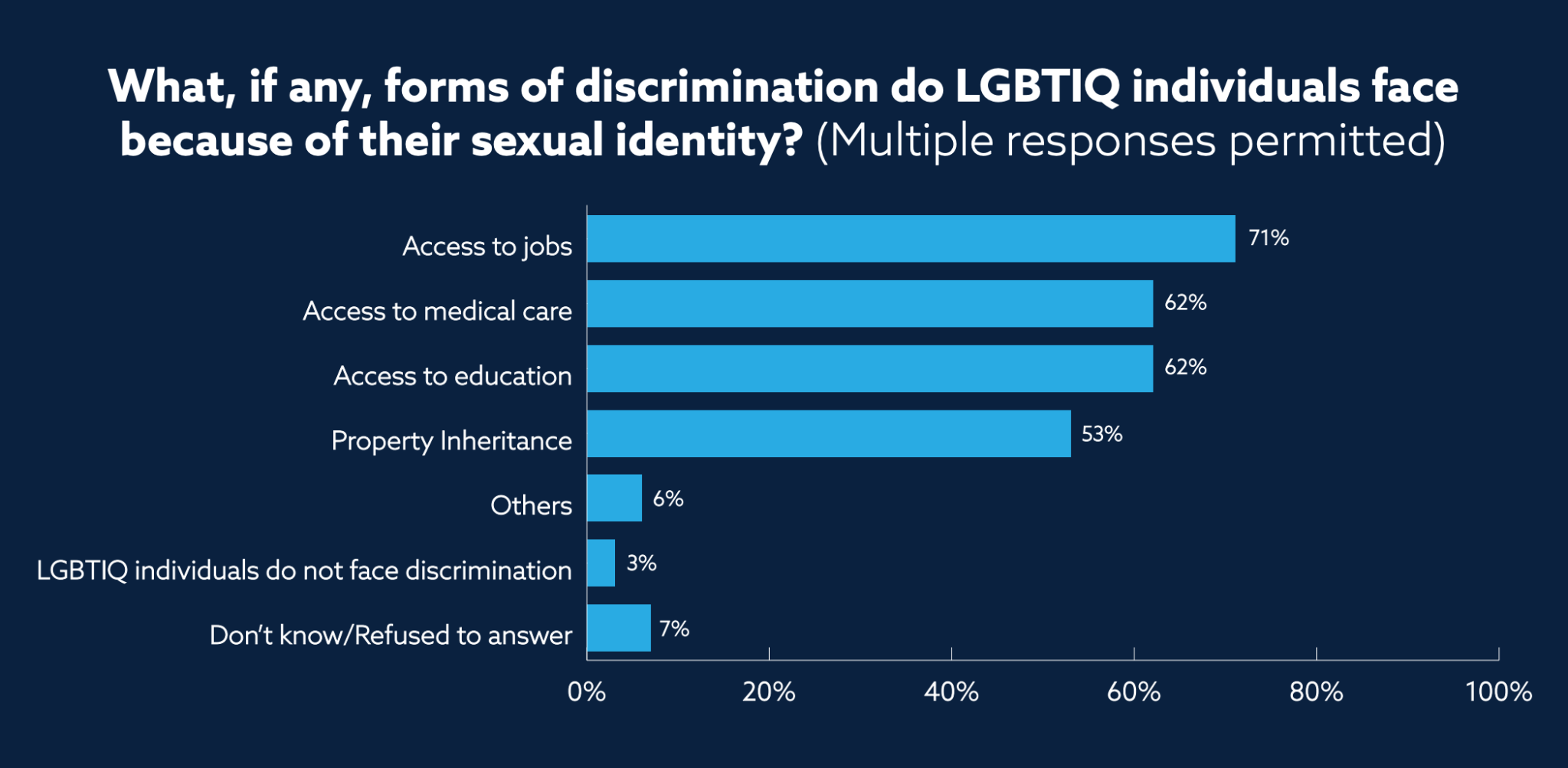

A large majority of survey respondents said they experienced multiple types of discrimination, including in access to jobs (71 percent), medical care (62 percent), education (62 percent) and property inheritance (53 percent). Only 3 percent of respondents said LGBTI people do not face discrimination. More rarely mentioned forms of intolerance included landlord discrimination, workplace harassment, exclusion from social events and denial of religious burial services.

FGD participants expanded on these and other issues.

When accessing healthcare, participants faced various problems including sexual assault or harassment, refusal of treatment and ignorance about sexuality and sexually transmitted diseases.

Homosexuality is still considered a disease in the medical sector. All the doctors see this as a disease, from perspective of their personal and social life as well as their conventional knowledge. So if you go to a doctor, he prescribes anti-psychotics for you. They consider it a mental disorder.

Gay Man

The doctors call this a disease. Once I went to a doctor with my mother. After seeing me, the doctor said to my mother, ‘Is your daughter normal?’

Lesbian

LGBTI people are often denied housing, are forced to pay above-market rent or are evicted if their sexual orientation becomes known. Only 14 percent of survey respondents lived in a house or apartment alone. Most still lived with parents (42 percent), friends (18 percent) or gurus (18 percent).10

These kinds of incidents happen even when we go to rent a house. If they get to know about us, they don’t give us rent. Even when they allow us, they give us the worst room with excessive rent. Also, they ask us to go away without providing notice.

Bisexual

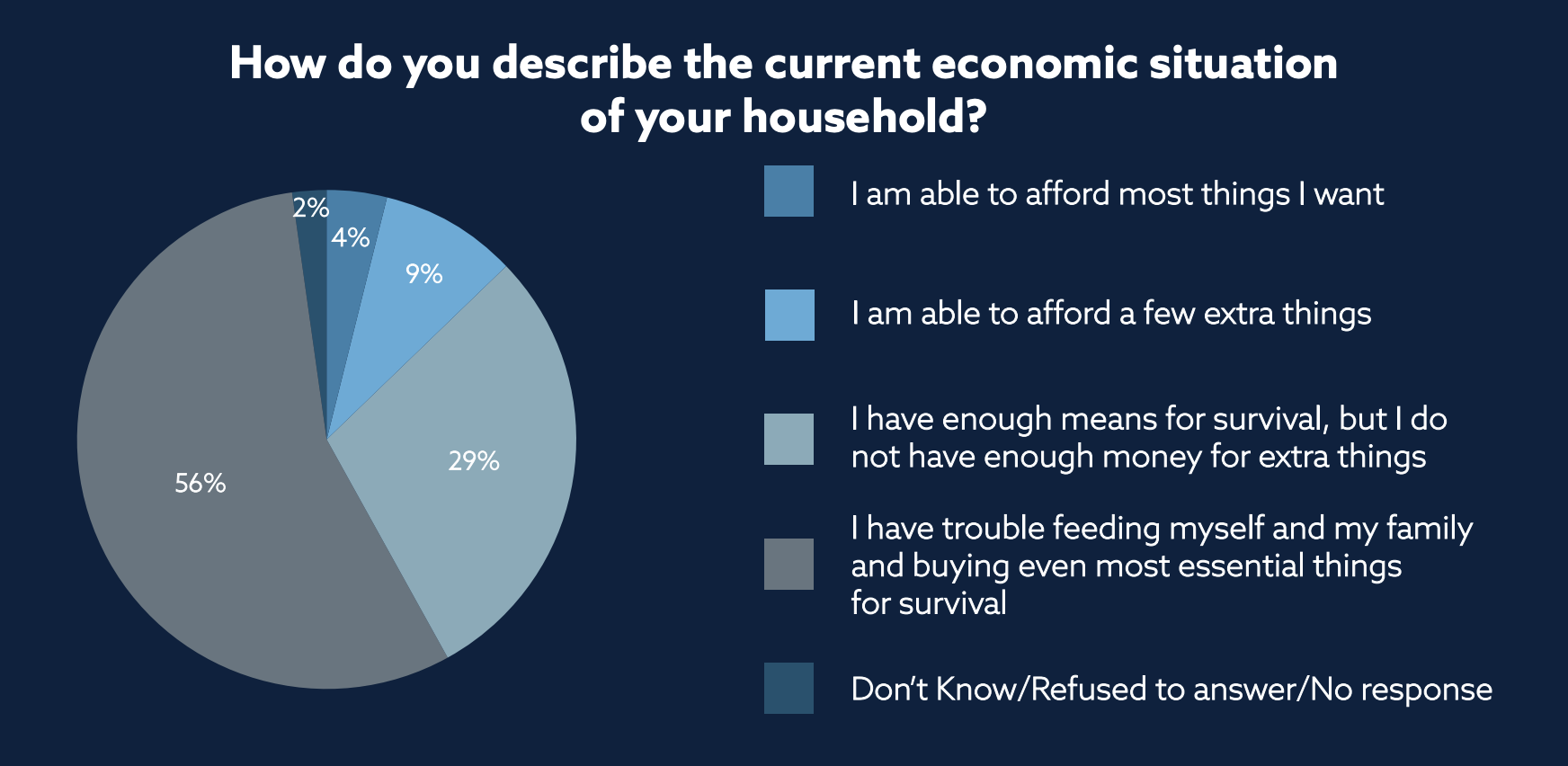

It is often difficult for LGBTI people to get jobs. Employers often do not want to hire gay men, bisexuals or lesbians. Many transgender women live on the street and lack the education and skills to get jobs. Other participants said that if they receive a job, they encounter sexual harassment or bullying from their co-workers. Intersex people face a different challenge: Government jobs require an applicant to note their sex, which is impossible for them. Fifty-six percent of survey respondents described their economic situation as “I have trouble feeding myself and my family and buying even the most essential things for survival.” Twenty-nine percent said, “I have enough means for survival, but I do not have enough money for extra things.” Only 13 percent said they could afford “a few extra things” or “most things I want.”

What we want is to be judged by our capabilities, not by our gender.

Man Who Identified as Queer

There is no scope for transgenders in the job sector. How will we get jobs then? We get jobs in NGOs, but not in government departments.

Transgender Woman

In the media, LGBTI people are rarely seen and, when they are, the portrayal is often negative. One participant said newspapers and media houses are under pressure from religious conservatives not to cover LGBTI issues.

They only show the bad things about us, not the good things. They don’t show our positive traits, but only the negative traits.

Transgender Woman

The gay community is being represented only as a part of mockery.

Man Who Identified as Queer

In primary and secondary school and at university, LGBTI students face myriad challenges. Most common is bullying from peers and teachers, but other issues undermine their academic achievement and mental health. Two transgender men participants said they lost points for refusing to wear a sari during a presentation. A lesbian participant said a professor denied her thesis topic on LGBTI issues. A gay man said his friend was kicked out of university when administrators discovered his sexual orientation. Across groups, LGBTI people said textbooks do not discuss LGBTI issues and classroom discussion rarely broaches these topics.

Many LGBT students are being subjected to sexual harassment. Because of this kind of sexual harassment, they cannot study properly for long.

Lesbian

Those who are a bit feminine face bullying more than others. My friend became the target of bullying numerous times … Ultimately, he felt forced to leave the school. He went to another school all because of bullying. He couldn’t find any friends … I came to know that he committed suicide.

Gay Man

Finding 7: Bangladesh’s legal system and police do not protect the interests of LGBTI people.

Bangladeshi law, specifically article 377 of the legal code, criminalizes same-sex intercourse. Therefore, many in the LGBTI community live in fear of arrest. A gay man explained, “During a get together, like the way we have gathered here, we have an uncomfortable feeling. If the police come, collect our identities, and want to arrest us, then they have the ability to do that. The law has given them that right.”

Because of legal prohibitions and social discrimination, the police have significant power over LGBTI persons. Several FGD participants in the transgender men group agreed: “If the police got the chance, they would kill us. And you are asking us about police protection?” Participants across groups said the police provide no or little protection and harass and blackmail LGBTI people. “I am a citizen of Bangladesh. It doesn’t matter who I am. [The police] have no right to speak to me in that manner. Why don’t the police speak in polite language? Why do they speak in such a way?”

Many participants said the police sexually assault gay and bisexual men and transgender women. “They don’t support us. They are only concerned about physical pleasure with us,” explained a transgender woman.” A gay man alleged, “We don’t [get support from the police]. They call us only for physical pleasure. They themselves call us.” Another gay man claimed his male friend ended a sexual relationship with a male police officer, after which the police officer had him arrested under article 377.

A bisexual man explained that LGBTI people do not want special treatment, only fairness. “To be honest, we want nothing,” he said. “The things we want, the police don’t have the power to give. If I tell him to pass a law that allows me to marry, he can’t do that. What we want is their lawful help … they have been blackmailing us while misusing their power.”

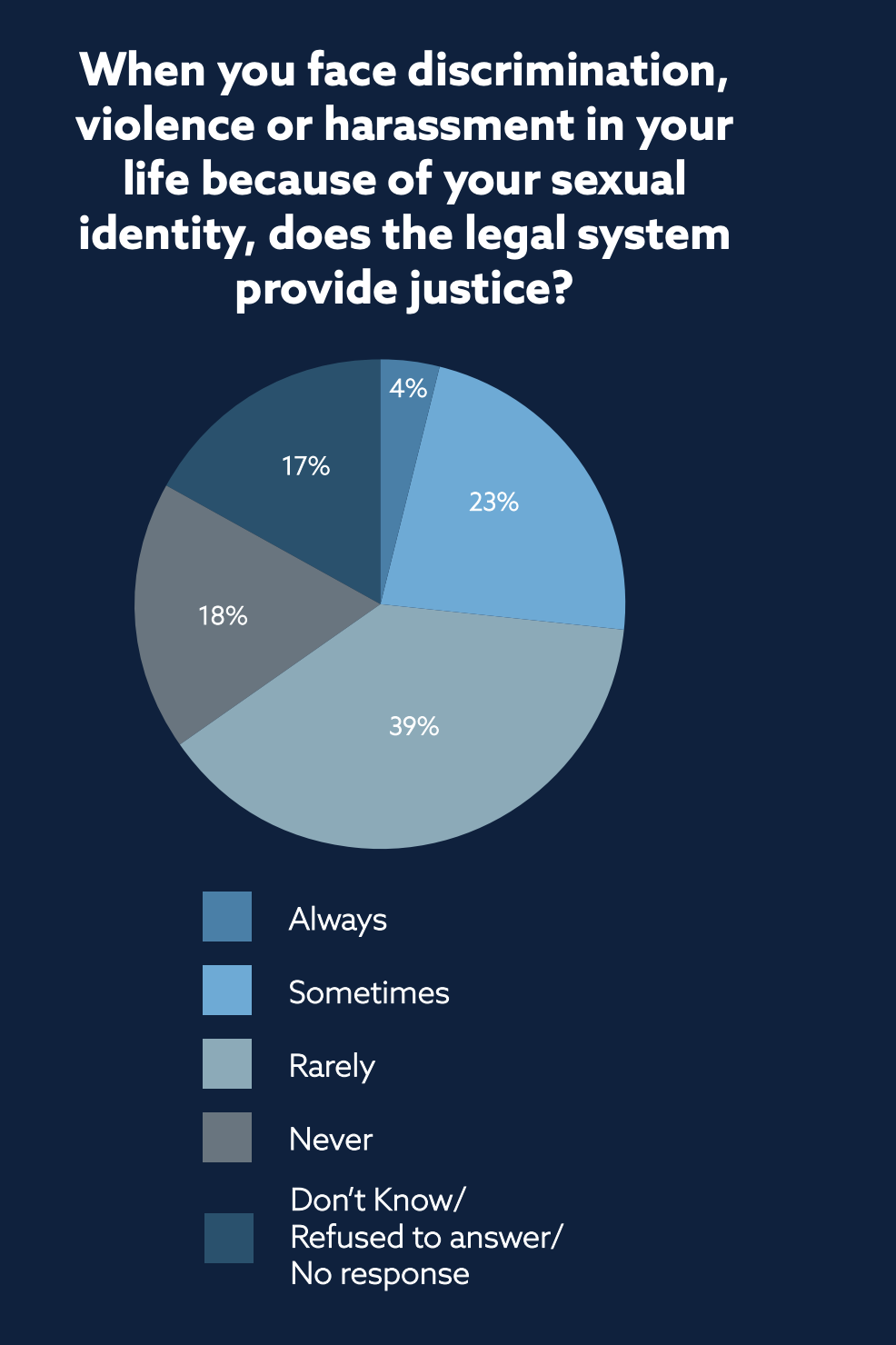

When asked in the survey if the legal system provides justice “when you face discrimination, violence or harassment in your life,” 57 percent of respondents said rarely or never, 23 percent said sometimes and 4 percent said always.

Finding 8: Politicians ignore LGBTI issues and LGBTI people have few avenues for support.

Most FGD participants said politicians pay little attention to the suffering of the LGBTI community because of negative political incentives in a conservative country. A bisexual man said, “This word [LGBTI] is prohibited for us to even say. It’s a very risky word to say. Because of the militant groups, Islamic movements, police force. And the Bangladesh government doesn’t ever accept us, let alone give us recognition. Although the government knows well that Bangladesh has a lot of people like us.” An intersex person explained, “Because Bangladesh is a Muslim country, if they support us, they will lose the election and they know this.”

Participants want the government to provide basic protections afforded to other citizens. A bisexual man said, “Everyone should get the same opportunities, the same rights. I want to have the same rights as other people. This is the only thing we want at first.” A transgender woman stated, “The last thing I want to say is please include us in government policies and make laws for us so that every ministry treats us with respect, that our human rights are not violated and all of our basic rights are fulfilled.”

Many participants explained that there is confusion within the government and society about LGBTI people, which undermines awareness about LGBTI issues. Because many government officials conflate intersex and transgender women, particularly Hijra, the unique issues facing intersex people are often ignored. Moreover, the government’s focus on transgender women has excluded others in the LGBTI community. A bisexual man explained, “The government only talks about transgender people and they won’t allow any other communities. There is no place for bisexual, homosexual and gay people. We can’t talk about ourselves anywhere.” Another bisexual man said, “Gay is different; lesbian is different; bisexual is different. Everyone has a separate sexual identity … But the government is failing to understand this. It’s their failure. But I cannot ignore my own identity for their failure.”

Because of the sensitivities and misunderstandings around LGBTI issues in Bangladesh, many LGBTI people have few avenues for help. An intersex person asked, “Where should we go? We have no one to help us.” A man who identifies as queer said that in severe cases, he will seek assistance from the police or government but “even asking for help gets us into trouble, so I do not do that unless the problem is a big one.” Most participants said they rely on other LGBTI people or NGOs for support with employment, housing, healthcare and counseling. “Those of us who belong to LGBTIQA community should work together,” concluded a bisexual man.

Conclusion

This study contributes to the understanding of Bangladesh’s LGBTI community. Although there is a significant effort among local activists, groups and researchers to collect the stories of and document the challenges facing LGBTI people in Bangladesh, there are few studies that deploy rigorous research methods. Limited funding and issue sensitivity have hindered research on LGBTI issues in Bangladesh. This focus group and survey study updates and expands the extant literature. Although FGDs and online surveys have clear methodological limitations, they offer unique insights into a community that is difficult to access. The findings suggest that LGBTI people in Bangladesh continue to suffer institutional discrimination, bullying, alienation, depression and physical and sexual violence. This research will assist LGBTI people in engaging in evidence-based policy advocacy with government officials.

Appendix

Top