Photo: Rashed Shumon/The Daily Star

“>

Photo: Rashed Shumon/The Daily Star

Two significant political events occurred in Bangladesh society between 1947 and 2024: the Bangladesh Liberation Movement of 1971 and the Anti-discrimination Students Movement of 2024. Both movements centered around the University of Dhaka. As a student of that institution from 1966 and a teacher up until now, my life—particularly my academic life—has been intertwined with the pulse of the university and these movements. I witnessed both movements as though I were a part of them.

The most striking feature of these movements was the differing role of intellectuals. During the Bangladesh Liberation Movement in 1971, most intellectuals were the driving force of the movement and, as such, became victims of oppression. On the night of 25 March 1971, the Pakistani forces planned to eliminate intellectuals, and on the night of 14 December 1971, over 200 intellectuals were rounded up in Dhaka and executed en masse. Thus, the Liberation War began and ended with the martyrdom of intellectuals. In contrast, during the Anti-discrimination Students Movement (also known as the anti-Fascist Movement) in 2024, most intellectuals were silent witnesses to oppression, supporters of fascist rulers, and willing oppressors of the students who led the movement. The intellectuals of Bangladesh thus became the beneficiaries of fascism. Consequently, the Anti-discrimination Students Movement began and ended with the martyrdom of students and the general public. This realization gave me an unsettling feeling about the mainstream intellectuals and instantly reminded me of Marx’s reflections on the coup d’état of December 2, 1851 by Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte: “Hegel remarks somewhere that all great world-historic facts and personages appear, so to speak, twice. He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce” (Karl Marx, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, 1852).

At the outset, it is important to clarify the meaning of intellectuals as distinguished from public intellectuals and the intelligentsia. Moreover, it is also essential to outline the role of intellectuals in other societies.

According to Raymond Williams in his Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society (1983), the intelligentsia is a status class composed of scholars, academics, teachers, journalists, and literary writers. The term was first used by Karol Libelt in 1844 and later by Bronisław Trentowski to describe Polish “inteligencja” (intellectuals), a professionally active social echelon of the national bourgeoisie with moral and political leadership in opposing the cultural hegemony of the Russian Empire in Poland. In pre-revolution Russia, the term “intelligentsiya” referred to a relatively autonomous group, united by common values and a sense of mission. Thus, ethical commitment to the liberation of the people from political and economic oppression was a necessary condition of membership in the intelligentsia. A half-learned student or a semi-literate peasant could become a member of the intelligentsia through participation in its liberating mission, whereas a conservative professor would be excluded as a supporter of reactionary forces.

Jeremy Jennings and Tony Kemp-Welch, in Intellectuals in Politics: From the Dreyfus Affair to Salman Rushdie (1997), define an intellectual as a person who engages in critical thinking, research, and reflection about the reality of society, and who proposes solutions to its normative problems. However, Thomas Sowell in Intellectuals and Society (2009) locates “intellectuals” as an occupational category, referring to people whose occupations primarily deal with ideas—writers, academics, and the like.

Sowell distinguishes between intellectuals and public intellectuals. Public intellectuals directly address the population at large, whereas intellectuals are largely confined to their respective specialties. At the core of the notion of an intellectual is the dealer in ideas: an intellectual’s work begins and ends with ideas. For example, some of the most impactful books in contemporary societies were written by Karl Marx and Sigmund Freud in the nineteenth century. However, these books were seldom read, and even less understood, by the general public. Yet, the ideas of Marx and Freud inspired vast numbers of public intellectuals worldwide, who in turn influenced the general public. Edward Said, in Representations of the Intellectual (1993), identified an intellectual’s mission as the advancement of human freedom and knowledge. Thus, the essence of public intellectuals is to engage with public issues, influencing public minds through criticism, popular writings, political commentaries, and prophecy.

Photo: Ziauddin Shiplu/The Daily Star

“>

Photo: Ziauddin Shiplu/The Daily Star

In post-1940 American society, as identified by Russell Jacoby in The Last Intellectuals: American Culture in the Age of the Academy (1987), the role of public intellectuals has been in decline. This trend is also observed by Michael Ignatieff in The Decline and Fall of Public Intellectuals (1997) for British society. However, with the advancement of digital technology in the West, public intellectuals have emerged in cyberspace, communicating with the public via the Internet, as Paul Ashdown discusses in From Public Intellectuals to Techno-Intellectuals: Gunslingers on the Cyberspace Frontier (1998). Another factor in the decline of public intellectuals in the West is the “bureaucratization of knowledge” in universities. James Smyth and Robert Hattam, in Intellectual as Hustler: Researching Against the Grain of the Market (2000), also point to the commercialization of academic work and market-driven consultancy and research as contributing factors. This situation is also seen among Bangladeshi academics. Recent changes in the curriculum and syllabi clearly show they are: (a) politically correct, (b) market-driven, and (c) NGOized. Consequently, post-1970 Bangladeshi intellectuals lost their emancipatory character and failed to play a significant role in the July-August 2024 Movement. They did not produce ideas like Marx, Gramsci, Stuart Mill, or Rousseau. In some cases, they became complicit in fascist political agendas, supporting police violence against unarmed student protesters.

Born during the Bengal Renaissance after the Permanent Settlement Act of 1793 and the English Education Act of 1835, Bengali intellectuals remained predominantly middle-class bhadrolok and communal. Their Indian nationalism crystallized into colonial forms: Hindu and Muslim nationalism. However, centered around the issue of cultural autonomy for Bengalis under Pakistan, a rudimentary form of Polish-Russian-type intelligentsia began to emerge. They opposed the cultural hegemony of Urdu in Pakistan. Thus, the Bengali intellectuals in East Pakistan were largely divided into two groups: hegemonic Urdu and counter-hegemonic Bangla. The quest for political autonomy originated in the cultural autonomy of the Bengalis. The apparent success of the Bengali intellectuals in organizing the Bangladesh Liberation Movement and forming the People’s Republic of Bangladesh led to their brutal killings by the Pakistani Army and their collaborators.

The massacre of the Bengali intellectuals led to a crisis among them soon after independence. Politicized intellectuals abandoned their oppositional role. Bengali fascism emerged under one-party rule (BAKSAL), and political killings of opposition forces began. The democratic state structure collapsed. Due to intellectual bankruptcy, there was no meaningful protest against it. There was no movement against the recolonization of Bangladesh and no movement for the restoration of democracy in the People’s Republic. Bengali intellectuals became thoroughly politicized and transformed into the ideological apparatus of the fascist state, which lasted from 1972 to 2024 under various guises.

In Western countries, public intellectuals mostly perform professional roles in society, while in developing countries, the limited opportunities for professional development encourage intellectuals to engage directly or indirectly in politics. To become beneficiaries, all administrations of public universities and University Teacher Associations during the BNP and AL regimes willingly embraced Friedrich Hayek’s The Road to Serfdom (1944). This led to the paralysis of criticism (Herbert Marcuse) in the nation and on campuses. Bangladesh became a one-dimensional, monolithic polity. The emancipatory intellectuals of the pre-independence era were metamorphosed into enslaved intellectuals in the post-independence era. Most of them joined fascism, as Erich Fromm described in Escape from Freedom (1941), betraying the promises of the Enlightenment.

In 1971, the intellectualization of Bangladesh suffered irreplaceable losses due to the Pakistan Army’s genocide. Between 1972 and 2024, the intellectualization of Bangladesh was ruthlessly suppressed by its own government. This is perhaps both a tragedy and a farce. It underscores the significant differences in the role of Bangladeshi intellectuals in two opposing movements with far-reaching consequences for the future.

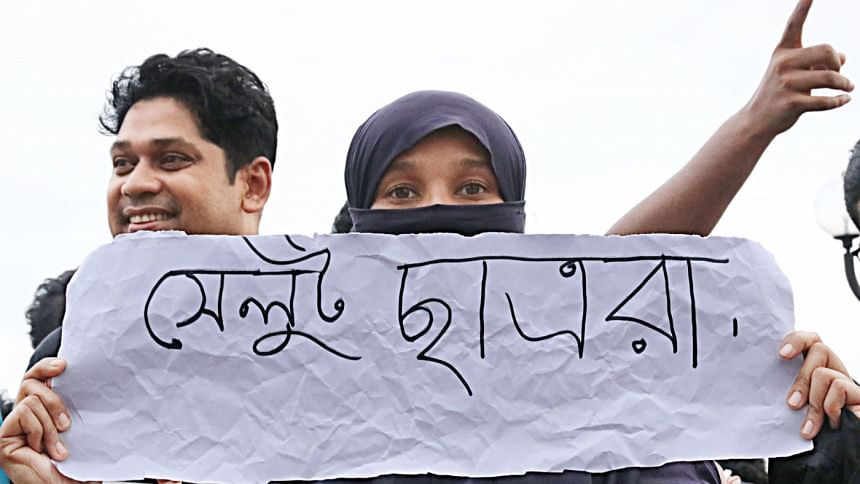

The dethronement of the ignominious Bangladeshi intellectuals during the Anti-Fascist Movement of 2024 clearly exposes their shameful role. When the protests were unfolding, fascist intellectual acolytes were maligning the students and spreading disinformation. In many universities, VCs and Proctors, in collusion with pro-government teachers, members of the Chhatra League, and the police, made students victims of brutal torture. Perhaps unwittingly, all our educational institutions, along with our non-emancipatory intellectuals, have embraced the “kiss of death.” We can observe many symptoms of intellectual barbarism and dying intellectualism since August. A country administered without ideas, and without the dealers of ideas (intellectuals), will become a stagnant state. If the future intellectuals of Bangladesh cannot restore their emancipatory role and only join the rat race for accumulating wealth, as before, they will push the country into a Hobbesian Leviathan.

A.I. Mahbub Uddin Ahmed is a professor in the Department of Sociology at the University of Dhaka.