January 28, 2025 • 2:15 pm ET

After the Monsoon Revolution, Bangladesh’s economy and government need major reforms

Table of contents

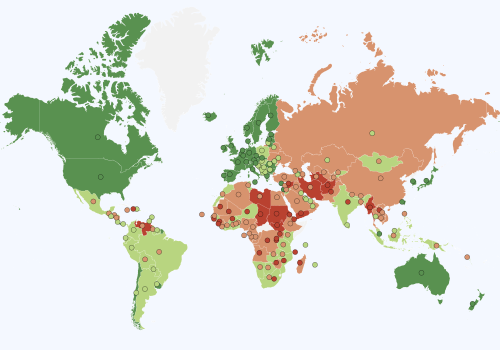

Evolution of freedom

Movements in the Freedom Index suggest that the institutional environment of Bangladesh has experienced substantial volatility since the 1990s. After the democratic revolution of the early 1990s, the country had a period of credible elections with relatively peaceful alternation of power between the two main Bangladeshi political parties, the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) and the Awami League. The Index shows a clear institutional deterioration during the 2000–08 period, coinciding with governance approaches by both major parties that appeared to intensify unhealthy political competition. In an environment with escalating corruption, the leadership and allies of both parties intensely focused on holding onto power at all costs, leading to increased political tensions. Widespread corruption by those in power became the norm, and both parties became increasingly eager to hold on to power by any means necessary. The main political tool employed by a marginalized opposition was to impede the functions of government. In particular, calling general strikes with increasing frequency (and of longer duration) became the political weapon of choice for the opposition, to signal their street-level organizational capabilities to the government and to citizens. The strategy was deployed to erode the dominance of the party in government, but it came at the expense of the citizenry because it disrupted economic activity and the freedom of movement. An extreme example was to call general strikes to coincide with important visits by foreign investors exploring investment opportunities. This was designed to weaken the government and undermine its ability to attract investment, and it came at a high cost to the country’s economic prospects.

Escalating corruption and this form of destructive political competition created a situation of increased political instability up to 2006, when scheduled elections could not be held, and a military-backed caretaker government remained in power for two years. The deep fall in the political subindex driven by a more than forty-five-point decrease in the elections component reflects this episode. The election score rebounds when elections that were widely considered free and fair were held in 2008. The Awami League received a supermajority as citizens used the 2008 election to express their deep discontent with the heightened corruption and misgovernance under the pre-2006 BNP regime. But the subsequent Awami League government, led by Sheikh Hasina, squandered the opportunity for improving governance. Instead, governance trends indicated a shift toward more centralized authority, as evidenced by a sustained decline in political and civil liberties scores. Examples of these autocratic tendencies include the abolition of the caretaker government system, widespread persecution of opposition political leaders accused of war crimes, and the rapid deterioration of citizens’ civil rights based on security concerns after terrorist episodes and an attempted military coup in 2012. Repression of both political opponents and ordinary citizens, more severe restrictions on speech, and increased government corruption became the norm. The Awami League exacerbated the type of misgovernance that had led the BNP to be voted out of office. Despite these concerns, the Awami League maintained in power for fifteen years amidst reports of increased political repression of citizens.

Elections held during the last fifteen years have been characterized by boycotts by the major opposition party and were not free or fair, so the relatively high election score assigned to Bangladesh in the political subindex is not an accurate reflection of the poor quality of politics and governance during this era. Elections followed a regular schedule, but it is difficult to see them as meaningful. Beyond the opposition election boycotts, the atmosphere of political violence and deep erosion of individual rights dramatically limited the level of contestation in the electoral process. Bangladesh’s extremely low score on legislative constraints on the executive partly explains why it was so easy for the Awami League to create an autocracy so quickly.

The legal subindex further confirms the erosion of the system of checks and balances necessary in a functioning democracy, clearly showing a negative trend in the two components that deal with the legal framework of the country: clarity of the law and judicial independence and effectiveness. The two-year caretaker government during 2006–08, and constitutional changes made by the subsequent Awami League government generated a state of legal uncertainty and insecurity. The twenty-point drop in the level of judicial independence since 2010 reflects the autocratic government’s efforts to control the judiciary to safeguard its hold on power and to use it as a weapon to persecute the opposition.

The improvement of the security component of stricter measures that curtailed some civil liberties. Mass protests and strikes, which were popular in the early 2000s, were no longer permitted, which resulted in a reduction in open street clashes and insecurity. But this also reflects political repression, so this clearly imposed costs on citizens. The data obviously do not yet reflect the mass student protests that began in July 2024, which ultimately resulted in the ouster of the autocratic government.

Also notable is the sustained improvement in Bangladesh’s informality score after 2005. The government made a big push towards digitalization of public services, including in tax administration. Digitizing third-party information improves the government made a big push towards digitalization of public services, including in tax administration. Digitizing third-party information improves the government’s ability to collect taxes, particularly Value Added Tax, which in turn limits firms’ capacity to operate in an informal shadow economy. This fact could also explain the small progress in bureaucracy and corruption observed in the data from 2004 to 2016, but it is important to stress that the level of this component is still exceptionally low for Bangladesh, not only creating discontent with the government and the state apparatus, but obviously generating substantial economic costs and inefficiencies.

Finally, the economic subindex evolution is driven by the movements in two components, namely trade and investment freedoms. The improvement in trade freedom in the late 1990s is a product of the adjustment programs imposed by the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank around this period, which forced a liberalizing process in several economic sectors. The ten-point fall in this component in 2013 is likely the result of stricter labor and workplace regulations implemented after the Rana Plaza disaster, which led to workplace injuries and deaths for hundreds of garment factory workers. Garment buyers in Bangladesh’s export destination countries pushed for these regulations. The sharp collapse of investment freedom between 2005 and 2008 is definitely capturing the political uncertainty of those years, and the rapid recovery when finally a government was formed captures the initial enthusiasm once the crisis was resolved.

It is important to comment on the surprisingly low level of women’s economic freedom observed in the data. Bangladesh scores almost eighteen points below the regional average in 2023, and the indicator only shows a mild improvement between 2007 and 2011. I think this might be explained by the distinction between the legal definition of women’s economic freedom versus actual practice. The real situation of women in economic affairs is probably better in Bangladesh than one would infer by looking at the formal legislation. For example, the Bangladeshi female labor force participation rate (39.5 percent) is significantly higher than in many neighboring countries such as India (29.9 percent) and Pakistan (25.9% percent), and the average for South Asia (30percent). The rapid expansion of the garment industry in the 1980s and 1990s created many new job opportunities, especially for women. That improved returns to education for girls, which led to greater investments in girls’ schooling. Bangladesh achieved the Millennium Development Goal of gender parity in educational enrollment by 1995, fifteen years ahead of schedule. Girls’ primary school enrollment has exceeded that of boys since then. As a by-product, early marriage and early motherhood have decreased dramatically. These improvements in women’s economic opportunities do not seem adequately captured by the legalistic approach embedded in the World Bank Women Business and the Law Index which determines the quantitative score on this component.

Evolution of prosperity

The positive evolution of the Prosperity Index fairly reflects the situation of the country in the last three decades. Despite the institutional volatility and bad governance, Bangladesh has outperformed most regional neighbors economically, and this has closed the prosperity gap, especially since 2014. Scholars have referred to this as “the Bangladesh paradox.” Early improvements in health and educational indicators created the preconditions for economic growth. Bangladesh’s health and educational achievements exceed what the country’s income per capita would predict. The country has made substantial progress in material wellbeing, and unlike some other countries in the region, has not suffered a major economic crisis in the last three decades.

The flat performance of the inequality component of the Index may reflect a lack of detailed data. Economic growth in the country has been obviously urban-biased, with increased activity in sectors such as construction and infrastructure that have benefited cities more than rural areas. Those sectors are also heavily prone to corruption and graft, leading to massive wealth accumulation at the high end of the income distribution.

The health and education components of the Index show that Bangladesh’s improvement has outpaced that of its regional comparators since 1995. While school enrollment has massively improved since 1995, a measure of average years of education does not adequately capture the quality of learning that happens in school. Learning and human capital remain important challenges for Bangladesh today. I suspect that a quality-weighted measure of education would not present as optimistic a picture.

Considerable progress has been made in the health sector, thanks to a determined commitment to ensure child vaccination and access to maternal and neonatal healthcare. A vibrant non-governmental organization sector in Bangladesh has played a positive role to deliver basic services. Again, the quality of healthcare remains poor, and there are emerging areas of concern such as worsening mental health—an issue that needs greater attention from policymakers.

I think the evolution of the environment score masks two opposing trends. Increased economic prosperity in rural areas expands access to cleaner burning cookstoves and other technologies that protect environmental health. Much of the population has remained rural, which probably drives the aggregate positive trend of the indicator. However, in urban areas, outdoor air quality has clearly worsened with increased manufacturing and construction activities (including emissions from brick kilns), and the attendant loss of green space. Increasing prosperity has also led to a proliferation of motorized vehicles and increased congestion, and a lack of urban planning has allowed the urban living environment to deteriorate. These detrimental effects are not adequately captured by the component.

The path forward

An autocratic government that had steadily consolidated its power was finally ousted by a student-led “Monsoon Revolution” during the summer of 2024. The revolution was diffuse and decentralized— with organic student protests that quickly spread throughout the country—and was not organized under the banner of any political party. As a result, the post-revolution political leadership and the way forward remain unclear. Dr. Muhammad Yunus, the founder of the Grameen Bank and a Nobel Peace Prize laureate, took charge as “chief advisor to the caretaker government” at the behest of students. His international name recognition and stature make him a credible leader, and temporarily stabilized the political uncertainty. But as I write, the country’s political future remains uncertain.

Given the political instability and challenges that Bangladesh has faced, citizens are willing to give an unelected caretaker government some leeway and time to govern and reform political institutions. For the moment, all parties, the military, and civil society appear to have implicitly agreed and acknowledged that the caretaker government should remain in power for at least eighteen months, so that they have sufficient time to institute reforms. But important sources of uncertainty remain unresolved. First, the political parties, and especially the recently-ousted Awami League, may pursue strategies to regain influence, which could lead to political instability. Misinformation propagated by right-wing groups in India seems deliberately aimed at destabilizing Bangladesh by inflating fears of religious conflict. However, the impact of these efforts is not yet clear. Second, to maintain legitimacy, the caretaker administration will have to perform, since it does not derive legitimacy from any election. Governing a country with a population of 175 million is a complex undertaking. The bureaucracy and other government institutions, including public universities, were reportedly subject to political influence during the Awami League’s administration. This makes reform even more complex. Third, the power of Bangladeshi political parties has traditionally stemmed from grassroots and street-level organization, with a power hierarchy that extends into rural areas. The caretaker government and the students who led the July 2024 Monsoon Revolution do not have the same political infrastructure and organization.

Bangladesh is in uncharted territory. There is a lot of hope among average citizens that ousting a powerful autocratic government was a major achievement, and that the architects of that uprising can ensure better governance going forward, by instituting some fundamental reforms and not repeating the mistakes of the past. Whether those hopes of a nation can be successfully realized remains to be seen. Given how fundamental many reforms need to be, including a re-examination of several aspects of the country’s constitution, the path ahead is likely neither linear nor straightforward.

Ahmed Mushfiq Mobarak is a professor of economics and management at Yale University and the founder of the Yale Research Initiative on Innovation and Scale (Y-RISE). Mobarak conducts field experiments in Bangladesh, Sierra Leone, and Nepal to investigate the adoption of welfare-enhancing innovations and behaviors, and the scaling of effective development interventions. His research has been covered by major global media outlets and published in journals across disciplines. He received a Carnegie fellowship in 2017 and was named in Vox’s inaugural list of “50 scientists working to build a better future.”

Statement on Intellectual Independence

The Atlantic Council and its staff, fellows, and directors generate their own ideas and programming, consistent with the Council’s mission, their related body of work, and the independent records of the participating team members. The Council as an organization does not adopt or advocate positions on particular matters. The Council’s publications always represent the views of the author(s) rather than those of the institution.

Read the previous Edition

2024 Atlas: Freedom and Prosperity Around the World

Twenty leading economists and government officials from eighteen countries contributed to this comprehensive volume, which serves as a roadmap for navigating the complexities of contemporary governance.

Explore the data

About the center

The Freedom and Prosperity Center aims to increase the prosperity of the poor and marginalized in developing countries and to explore the nature of the relationship between freedom and prosperity in both developing and developed nations.

Stay connected

Image: A view of vehicles stuck in traffic on Mirpur road in the New Market area, Dhaka, Bangladesh, October 7, 2024. REUTERS/Mohammad Ponir Hossain

Keep up with the Freedom and Prosperity Center’s work on social media