Inflation persistence and structural breaks

In the literature, there are multiple interpretations of inflation persistence. Batini and Nelson (2001) consider three types of persistence: (1) positive serial correlation in inflation, (2) lags between systematic monetary policy actions and their peak effect on inflation, and (3) lags between inflation responses to non-systematic policy actions (i.e., policy shocks). According to Marques (2004), the first type cannot be considered an acceptable definition, whereas the other two types are acceptable, following Willis’ (2003) definition of persistence as the speed of convergence. A higher speed of convergence indicates lower persistence, and vice versa.

Inflation persistence is an important factor in understanding the output costs of reducing inflation back to target, also known as the “sacrifice ratio.” The greater the policy space, or the monetary policy’s flexibility to handle transitory price shocks, the lower the persistence. Countries with high persistence and limited policy space may have to make significant changes to macroeconomic policies in response to the shocks, as they can affect both inflation and inflation expectations for a long time (Roache, 2014). It is important to note that there is a difference between reduced-form persistence, an empirical characteristic of the inflation time series, and structural persistence, which arises from observable macroeconomic factors such as monetary policy behavior or output (Fuhrer, 2011). Recent empirical investigations have focused on the relationship between macroeconomic drivers of inflation persistence and inflation dynamics. The findings suggest that reduced-form persistence has declined in recent years, in line with the implementation of successful inflation-targeting regimes that have permanently decreased persistence. However, there is a lack of research on inflation dynamics in developing nations, where inflationary shocks tend to be more persistent in the absence of inflation-targeting policies and proper inflation expectation anchoring (Ha et al., 2019).

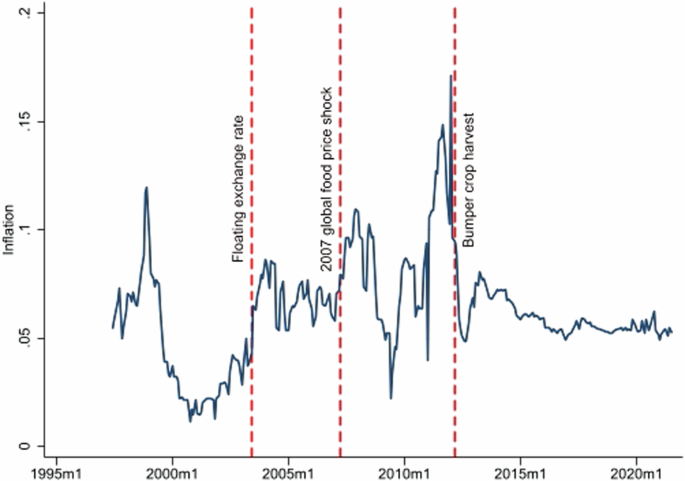

In the post-World War II period, inflation showed a high level of persistence, close to that of a random walk. This implies that central banks would need to take a more aggressive approach to restore inflation to its target than if there were low persistence. However, this high persistence should be considered an indicator of unconditional inflation persistence since the data generation process of inflation is composed of different components, each with its persistence level. Numerous factors contribute to the persistence of measured inflation over time. One of these factors is the significant shifts in the monetary policy strategies that have occurred over the last decades in both developed and developing economies. Central banks have been shifting their inflation targets and management policies, introducing nonstationary components into the observed inflation series. To provide a reasonable estimation of the various types of inflation persistence, these shifts should be explicitly accounted for since changes in the central bank’s inflation objective have a long-term effect on inflation. As a consequence of these shifts, the observed inflation persistence is biased toward non-rejection of the unit root hypothesis when using a standard autoregressive model. This argument was first presented by Perron (1990), who showed that the traditional Dickey-Fuller unit root test is biased toward non-rejection of the unit root hypothesis when the genuine data-generating process has broken in its deterministic components.

Therefore, it is important to identify the presence of structural breaks using suitable econometric methods to estimate the level of inflation persistence accurately. Without identifying structural breaks, conclusions drawn regarding the degree of persistence of inflation may be erroneous. Moreover, these conclusions will depend on the specific method used for testing breaks, as different procedures can result in different break dates or even varying numbers of breaks (Oliveira and Santos, 2008). One of the most widely used tests for detecting multiple structural breaks in empirical studies is the Bai-Perron sequential break test (Bai and Perron, 1998; 2003). However, the literature mentions several drawbacks of this test, particularly when dealing with small samples and variables with high serial correlation. The requirement of a trimming factor (minimum segment length) in the test leads to a reduction in the number of observations available for determining the date of structural breaks, artificially reducing the number of potential breaks, especially near the beginning and end of the sample period (Oliveira and Santos, 2008). Despite these limitations, the Bai-Perron test remains one of the most widely used techniques to study the presence of multiple structural breaks.

Among the measures used in the literature for measuring inflation persistence, the sum of coefficients of an autoregressive model and spectral density at zero frequency is the most widely used and reliable method for measuring inflation persistence (Pivetta, Reis (2007)). These measures tend to provide similar results over a fixed sample period. However, the half-life method and largest autoregressive root often provide a measure of persistence that deviates from the correct measure of persistence. Khundrakpam (2008) studied inflation persistence in India over the period 1982–2008 using the sum of the coefficients of the autoregressive model. The study found that inflation persistence tended to be lower when the model allowed for the structural break. Using the same method, Gerlach and Tillmann (2012) studied the inflation persistence in Asia-Pacific following the Asian Currency Crisis in 1997–1998. They found that countries that adopted inflation targeting experienced lower persistence, while countries that did not adopt inflation targeting experienced a persistence similar to pre-crisis levels, highlighting the role of monetary policies in curbing the impact of a shock.

Among other measures of inflation persistence, several studies apply long-memory processes, including the auto-regressive fractionally integrated (ARFIMA) model. Baillie et al. (1996) studied the inflation persistence of 10 countries using an ARFIMA-GARCH model and found strong evidence supporting long memory except for Japan. They also found evidence supporting the Friedman hypothesis (which posits a positive relationship between inflation and inflation uncertainty). However, one of the most common methods of measuring persistence is the AR(1) method (Kumar and Mitra, 2012).

Current empirical research has started to address the issue of structural breaks and time-varying persistence. While some studies do not consider structural breaks while estimating the persistence level (e.g., Lu and Zhang, 2003), studies like Gerlach and Tillmann (2012) investigate the possibility of a shift in persistence by using rolling regressions. Some papers conduct a bootstrap method to examine the presence of structural breaks in the variable of interest (i.e., Chan and Matos, 2010). After the introduction of the Bai-Perron (1998, 2003) test for identifying multiple structural breaks, more than one break was found in inflation. Moreover, the magnitude of persistence decreased overall and showed significant fluctuations after the shifts were included in the model (Capistran, Constandse (2009)). However, using the Narayan and Popp (2010) unit root test, Devpura et al. (2021) found time-varying inflation persistence and statistically significant structural breaks for 36 Asian economies. One of the interesting findings of the study is that changes in monetary policy regimes and the global financial crisis resulted in statistically significant structural breaks for respective countries. Using a time-varying parameter vector autoregression (TVP-VAR) model, Dua and Goel (2021) found that supply shocks, exchange rate shocks, and food shocks have a significant impact on inflation persistence in India, whereas interest rate shocks are not so important.

When policymakers aim to reduce inflation persistence, it is important to identify the different sources of persistence. Several empirical studies show that expectations regarding inflation and changes in the monetary policy regime significantly influence inflation persistence. Gerlach and Tillmann (2012) found that inflation targeting has significantly reduced inflation persistence in the developing economies of Asia-Pacific and South Africa, except for Indonesia. They also found that persistence did not drop in the countries that did not adopt inflation targeting. Furthermore, significant inflation persistence is observed when fiscal dominance coexists with long-term money supply growth or when prudent anti-inflation policies are not followed by a credible decrease in budget deficits (Boyd and Smith, 2007). According to Bilici and Çekin (2020), unusually high and persistent inflation can also be primarily a result of the political scenario, resulting from hikes in public sector prices and the weakening of exchange rates, as can be seen in the case of Turkey.

Inflation and inflation uncertainty

Uncertainty surrounding inflation is a significant problem in both emerging and developed economies as it affects various macroeconomic variables, such as interest rates and exchange rates, which, in turn, affect the real and nominal activities of an economy. In particular, it has a greater impact on emerging market economies where inflation uncertainty can adversely affect economic development and real net revenues (Terzioğlu, 2018). The COVID-19 pandemic has brought inflation uncertainty to the forefront of attention for policymakers and market participants, as large spikes in uncertainty are impacting financial markets and the broader economy.

Armantier et al. (2021) examine how household inflation beliefs evolved during the first six months of the COVID-19 pandemic. They find that the pandemic had a muted impact on average inflation expectations, though short-term expectations increased significantly. The crisis immediately elevated inflation uncertainty and disagreement at both medium-term and short-term horizons. The authors also observe substantial polarization in beliefs, particularly in the short term. A significant portion of households initially perceived the pandemic as inflationary, while others, especially those with a college education, anticipated low inflation or deflation. Ha et al. (2019) claim that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has intensified high inflation pressures, prompting central banks to raise interest rates. Although inflation is expected to return to target levels in the medium term, the experience of the 1970s underscores potential risks. Advanced economies may need to implement more aggressive monetary policies to bring inflation back to target. This approach could increase borrowing costs for emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs), which are already struggling with high inflation before fully recovering from the pandemic.

Numerous empirical studies have examined the relationship between inflation and inflation uncertainty, and the literature presents two different viewpoints on this inflation-uncertainty nexus. Friedman (1977) suggested that an increase in inflation leads to inconsistent policy responses from monetary authorities, resulting in greater inflation uncertainty, which, in turn, negatively impacts output, and this is known as the Friedman-Ball hypothesis. On the other hand, Cukierman and Meltzer (1986) hypothesized that inflation uncertainty causes an increase in inflation, while Holland (1995) found a negative relationship between inflation uncertainty and inflation.

For emerging markets, Thornton (2007) found a significant positive relationship between inflation and inflation uncertainty using a GARCH model over the sample period from 1957 to 2005. Daal et al. (2005) used the asymmetric PGARCH model to examine the Friedman-Ball hypothesis for developed and developing economies and found that inflationary shocks have a greater impact on inflation uncertainty in Latin American countries than in developed economies. Chowdhury (2014) analyzed the relationship for India and found support only for the Friedman-Ball hypothesis.

Recent literature examines the inflation-inflation uncertainty nexus in time-varying settings and considers structural breaks. Apergis et al. (2021) found that inflation causes inflation uncertainty only when the country experiences high inflation after allowing for structural breaks in the inflation series for Turkey. Barnett et al. (2020) found a positive relationship between inflation and inflation uncertainty during the short to medium run when the economy is stable and a negative relationship during a crisis. Overall, the relationship between inflation and inflation uncertainty remains ambiguous in the literature.

Westhuizen et al. (2023) investigate the relationship between inflation uncertainty and inflation outcomes in South Africa, focusing on the country’s adoption of inflation targeting in 2000. Their findings show a bi-directional relationship, with strong support for the Friedman-Ball hypothesis and weaker evidence for the Cukierman-Meltzer hypothesis. The implementation of inflation targeting has significantly reduced both inflation and uncertainty since its adoption. In the decade preceding targeting, increased uncertainty led to higher inflation. Musa (2022), using Consumer Confidence Survey data from Pakistan for the period January 2019 to March 2021, demonstrates that the COVID-19 pandemic has positively affected inflation expectations and volatility. In Pakistan, the pandemic’s impact on consumer confidence increased uncertainty and risk associated with inflation, resulting in increased volatility. Musa’s study of Pakistan emphasizes that policymakers must closely monitor inflation expectations to prevent un-anchoring risks and maintain the resilience of the real economy.