Sheikh Hasina may have made a dramatic exit following the youth-led mass uprising on August 5, but the legacy of her 15-year autocratic rule will likely haunt Bangladesh for months—if not years—to come. Her fallen regime has left behind a flailing economy, institutions that have been hollowed out from inside, a culture of corruption at all levels, and an aggrieved populace who have been suppressed through various means over the years. The interim government, which took charge on August 8, faces the mammoth task of not only bringing back economic, political, and social stability at a time of great turmoil but also introducing major reforms to democratise state institutions and ensure that the corrupt rule of one party is not replaced by that of another. That is easier demanded than delivered.

Over the last decade, the Awami League placed its supporters in top positions in all state institutions, consolidated its power, and enabled rampant corruption to take place without any accountability. The sudden fall of the once invincible regime triggered a wave of resignations, dismissals, or reshuffles within branches of law enforcement, the administration, the bureaucracy, and public universities and colleges across the country. While many top officials stepped down of their own accord or went into hiding, others were forced to do so amid widespread and, at times, aggressive, protests and demands from students, colleagues, and/or subordinates

The ensuing chaos within public institutions has led to the disruption of regular activities and services and created perfect conditions for supporters of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) and other opposition parties to mobilise and strengthen their own position within organisations in which they had long been sidelined. In the health sector, for example, as many as 173 doctors who were recruited during the BNP regime and deprived of promotions throughout the Awami League’s rule were all promoted in one single day. Meanwhile, frustrated officials, including Bangladesh Civil Service cadre, who were denied promotions or placements of their choice for political reasons or poor track records, have been agitating outside the ministries in the Secretariat almost every day since the interim government took over, demanding an immediate resolution of grievances.

A festering crisis

How will the interim government address this festering crisis? On the one hand, it cannot turn a blind eye to the unbridled corruption that has seeped into every sphere or public service. It must take exemplary action against all those involved in such practices, which is likely to include a huge number of public servants affiliated with the erstwhile ruling party. On the other hand, it cannot simply replace the loyalists of one party with those of another, giving in to populist demand, if it is to end the cycle of partisanship that lies at the root of ailing public institutions. For now, the strategy of the interim government remains unclear.

Muhammad Yunus, Nobel laureate and Chief Adviser of Bangladesh’s interim government, in Dhaka on August 13.

| Photo Credit:

INDRANIL MUKHERJEE/AFP

While it weighs its options, the BNP and its members are already jostling to establish their claims over the power structure(s) at the local and national levels. Reports suggest that BNP-affiliated men have taken control of major transport organisations, bus terminals, and workers’ unions across the country, seemingly to get their share of the 2,000 crore taka collected by the transport owners’ and workers’ associations through extortion across the country annually. Extortion is also going on in full swing in the slums and pavements of the capital, with politically backed gangs exerting their muscle power to grab shanties, shops, clubs, and offices. This is the scenario in almost every sector in the country.

Also Read | Power has shifted in Bangladesh, but old habits die hard

It is also concerning that murder cases are being filed in an indiscriminate manner against the former Prime Minister, Awami League leaders, judges, lawyers, scholars, journalists, and even a cricketer, without any specific evidence. While it is of critical importance that those who participated in a range of criminal activities during the Awami League tenure are held to account, and justice ensured for the mass murders during the July uprising, legal experts have pointed out that there should be specific allegations and, more importantly, evidence to ensure credible investigations and convictions. Not only do such cases reek of the kind of political witch hunt that the Awami League government itself conducted against its opponents, but they also undermine the murder cases and do the victims a great disservice.

“Whether or not Bangladesh can finally set itself on a new course depends on whether its policymakers and people are willing to learn from the past and ensure true accountability.”

As the human rights activist and Supreme Court of Bangladesh lawyer Sara Hossain noted: “The people might have genuine anger and frustration, but filing cases this way will not work. They will not sustain and may even fail to go beyond the initial stages. Rather, the cases are calling the movement and its outcome into question.”

The investigative journalist David Bergman has further observed that the cases filed have less to do with the bereaved families and more to do with BNP/Jamaat-e-Islami lawyers taking over the process. “From all their rhetoric over the last 15 years, one might actually have thought the BNP/Jamaat were against the politicising of the criminal justice system. Now they have power, we can see that is clearly not the case,” he wrote in a recent social media post.

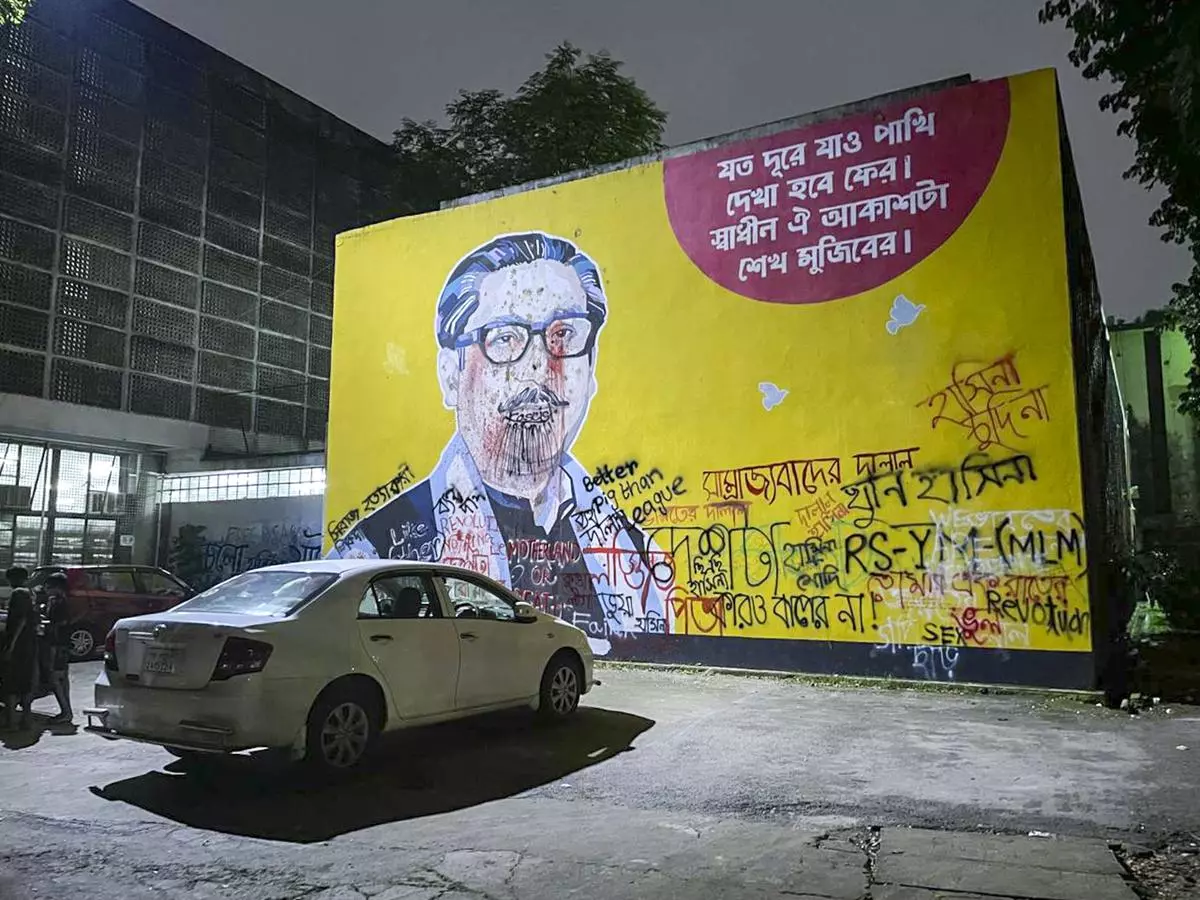

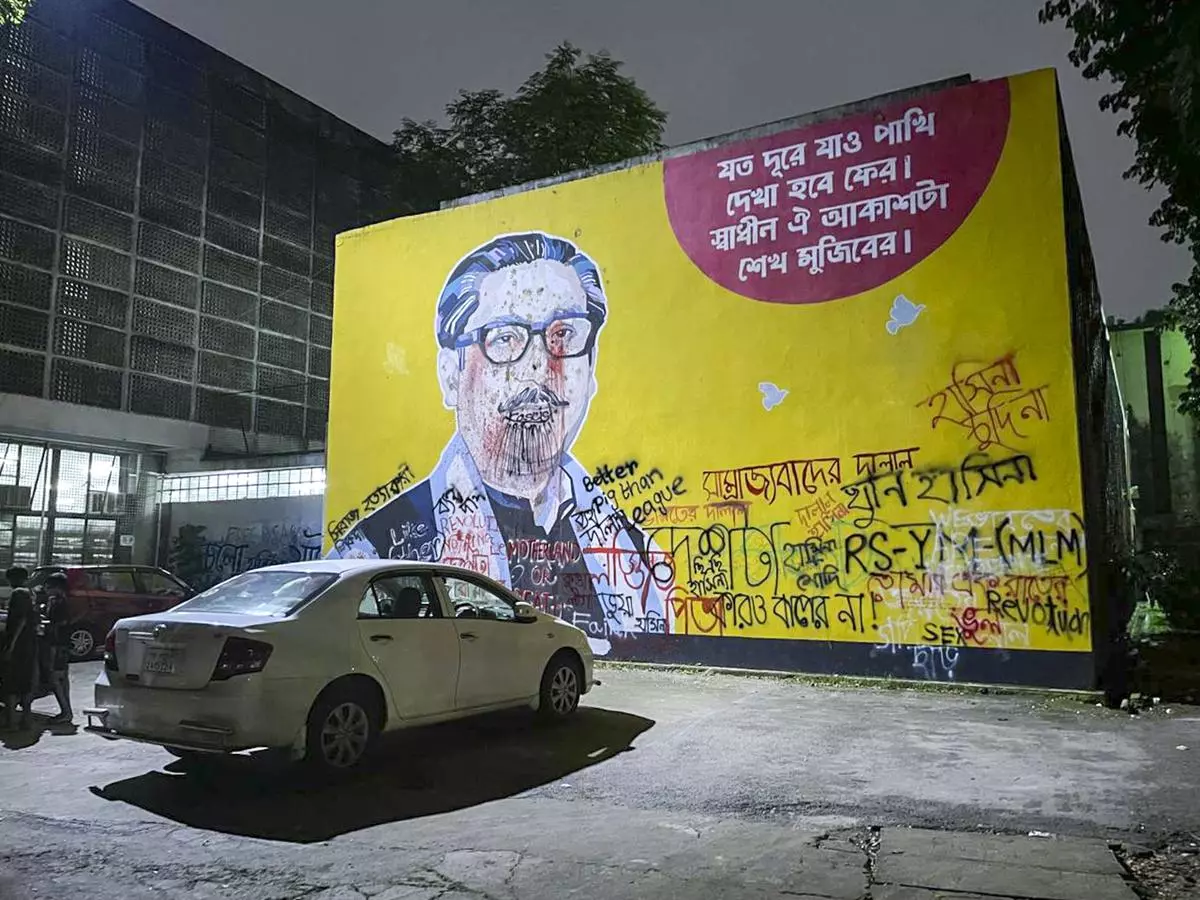

A mural celebrating the legacy of Bangladesh’s first President, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, defaced with graffiti, in the Dhaka University campus.

| Photo Credit:

Kunal Dutt/PTI

There have also been instances where pro-BNP and Jamaat lawyers and supporters have assaulted the accused in police custody in the court premises, including former Social Welfare Minister Dipu Moni, retired Justice AHM Shamsuddin Chowdhury, president of the Jatiya Samajtantrik Dal Hasanul Haq Inu, and president of the Workers Party of Bangladesh Rashed Khan Menon. Such blatant politicisation of the legal process—which multiple advisers, including the Chief Adviser himself, have faced and criticised during the Awami League rule—will only undermine the neutrality and commitment of those tasked with ensuring a radical change in political culture.

Highlights

- Sheikh Hasina’s sudden exit has left Bangladesh reeling, with institutions in disarray and a scramble for power threatening to replace one partisan regime with another.

- The interim government faces the Herculean task of reforming hollowed-out institutions while navigating a minefield of populist demands and entrenched corruption.

- As the BNP muscles its way back into the power structure, the promise of true reform hangs in the balance, leaving Bangladesh at a critical crossroads between meaningful change and a return to dynastic politics as usual.

Same cycle of repression and corruption likely

It is apparent that without the reforms demanded by the mass uprising, we risk going back to the same cycle of lawlessness, repression, and corruption, only with different victors. The BNP has insisted that long-term reforms can be delivered only by an elected government, urging the interim one to immediately unveil a road map for elections. On August 24, BNP Secretary General Mirza Fakhrul Islam Alamgir said: “Elections are crucial for reforms that have come to the forefront. Because [without elections] how will the reforms be completed? These will be done through an elected parliament. There is no alternative.”

Bangladesh Nationalist Party supporters at a rally in Dhaka on August 7. The party, along with the Jamaat-e-Islami, is now back in the reckoning in the country’s politics.

| Photo Credit:

RAJIB DHAR/AP

On August 25, Muhammad Yunus laid out his vision of reform in his first televised address to the nation, which included forming a police commission to overhaul law enforcement; a bank commission to reform the financial sector; comprehensive reforms in education, administration, health, agriculture, judiciary, and the electoral system; empowerment of local government bodies; and reforms to ensure free flow of information. He also stated that he had instructed the security forces to identify and bring to justice those who were directly involved in enforced disappearances, extrajudicial killings, or torture over the past decade(s), including during the July uprising.

The reforms he mentioned in his speech are what the nation desperately needs and what he himself identified as “the bare minimum” needed to bring the country back on track. But the critical questions remain: can his government really deliver what successive governments, including prior caretaker governments, have failed to do since the country’s independence? Equally importantly, how long would he need to institute these lasting reforms that, for all practical purposes, would require years to yield results?

Also Read | India’s offer to finance Teesta barrage puts Prime Minister Hasina in a diplomatic fix

Yunus was diplomatic in his answer about his tenure. “Everyone is eager to know when our government will depart. The answer lies in your hands. It is up to you to decide when to bid us farewell,” he said, adding that when the elections will be held is “completely a political decision”. However, he offered no specifics on how the interim government would engage with the entire electorate or gauge the pulse of the people who, despite uniting over the demand for Sheikh Hasina’s resignation, now hold vastly different visions for the future. There is also the unresolved issue of who will represent the progressive centre/Left in Bangladesh with the undoing of the Awami League and the co-opting or weakening of the Left over the past decades.

While assurances of pro-people reforms and the prioritisation of the people’s will are what the Bangladeshis want to hear, especially after years of frustration with not only Awami League rule but also predatory dynastic politics and crony capitalism since the 1990s, the reality is that they have heard such promises before. Whether or not Bangladesh can finally break free of its curse and set itself on a new course depends on whether its policymakers and people are willing to learn from the past and ensure true accountability moving forward.

Sushmita S Preetha is the op-ed editor of The Daily Star, a leading English language newspaper in Bangladesh.