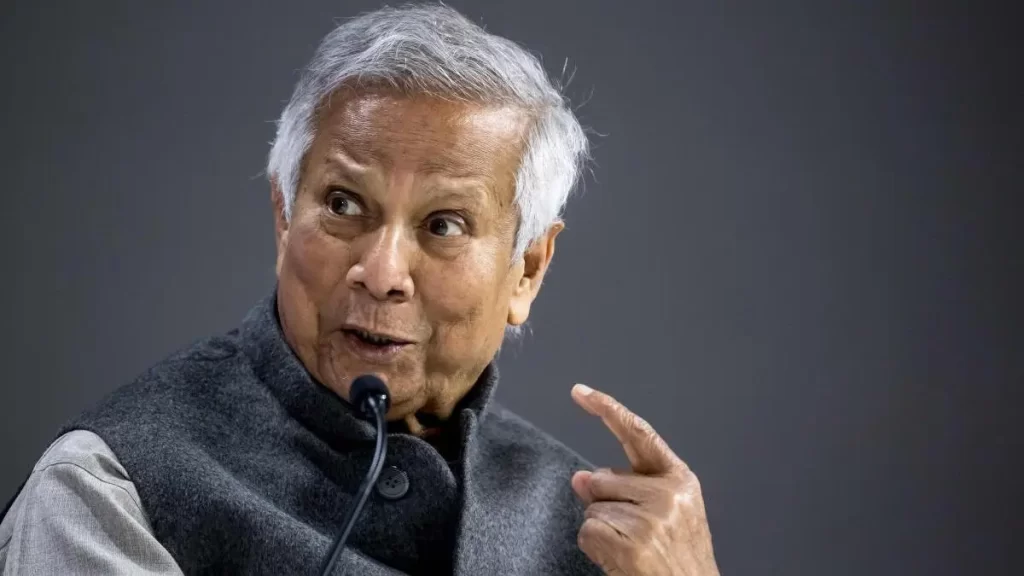

Yunus speaks at a session during the World Economic Forum (WEF). The promise of renewal after Sheikh Hasina’s fall has given way to instability. With stalled elections, political bans, and military interference, Bangladesh risks slipping into deeper authoritarianism under a caretaker regime.

| Photo Credit: FABRICE COFFRINI / AFP

Ten months after the ouster of Sheikh Hasina from office and her flight to India, Bangladesh continues to be poised on the edge of dangerous uncertainty. Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus, hailed in the wake of Hasina’s exit as the most appropriate Bangladeshi to put the country back into shape, has not lived up to that expectation. His skills as a banker have proved inadequate to managing a country where expectations were sky-high that the departure of an authoritarian and allegedly corrupt leader would lead to a new dawn, and people are angry and puzzled that this has not happened.

At the most basic level, the Yunus-headed interim administration has been unable to restore law and order in the country. Mobs and vandals rule the streets. Every section of society, from the youngest to the oldest, has its own demands, and they are making themselves heard through protests.

Yunus’s main focus as the chief administrator of the interim set-up should have been to hold elections. While he has taken up with gusto other policies, such as foreign affairs that should fall in the remit of an elected government, the timetable for an election to replace the ousted Awami League government remains vague. The Jamaat-e-Islami, banned by the Hasina government and reviled even now for its collaborationist role with the Pakistan Army in 1971, has been allowed to function once again. The ban on it has been lifted, and the ground has been paved for its re-registration as a political party. It wants the elections to be held as late as possible, as it strengthens itself on the ground.

Also Read | India and Bangladesh are destined to work together: Sreeradha Datta

The newly formed National Citizens’ Party of students who led the protests against Hasina last year also wants elections delayed until after constitutional reforms are carried out, though such changes will need the widest possible support, which only an elected Parliament can ensure.

On the other hand, the Bangladesh National Party (BNP), out of power for two decades, for most of this period due to questionable elections during Hasina’s watch, senses its first chance of making a political comeback since 2006. Naturally, it wants the elections by the end of this year. In this, it has the support of the Bangladesh Army.

Corridor to Myanmar

The Army, which backed the setting up of an interim administration, has also voiced concerns at some of Yunus’s decisions. One of these, an apparent decision to carve out a humanitarian corridor from Bangladesh to Myanmar for the stated purpose of helping Myanmar’s Rohingya community (over a million live in refugee camps at Cox’s Bazaar in Bangladesh, and more continue to pour in) appeared to bring the country to the brink of another breakdown. The Army chief, General Wakar-uz-Zaman, who is a Hasina appointee, made clear his unhappiness with the decision which, as he told his officers in a speech that was made public, impacted on national security.

The Bangladesh Army was alarmed by the decision for several reasons. One, it feared that it would give opportunities for the Arakan Army, which is fighting the Myanmar army and has wrested almost all of the Rakhine state from the junta, to seek strategic depth in Bangladesh. This would bring the Bangladesh defence forces into direct conflict with Myanmar’s ruling dispensation, however illegitimate it might be. It would also create space for the Arakan Salvation Rohingya Army, which is banned in Myanmar as a terrorist group and is active in the refugee camps.

Then, suspicion was rife that the US and other Western governments were behind the idea of the “corridor” with a view to using it as a supply route for the AA and other people’s militias and armed ethnic organisations fighting the junta. That the idea came from a newly appointed National Security Adviser—Bangladesh has never had one, and an interim administration’s decision to appoint one has puzzled observers—fuelled this apprehension further.

It was against this fraught background that in the last week of May, Yunus floated a threat to resign on account of the pressures being mounted on him. He has since withdrawn this threat, and talk of the so-called humanitarian corridor has also subsided.

What remains is the demand for elections by December this year by the BNP and the Army. The Army chief also reportedly conveyed the importance of an “inclusive” election, conveying to the Yunus administration that the Awami League must be allowed to participate.

The Awami League has been banned. The International Criminal Tribunal that was set up by Sheikh Hasina to try members of the Jamaat accused of collaborating with the Pakistan Army during the Liberation War is now being used to try her and members of her party. On June 1, the ICT charged the former Prime Minister with crimes against humanity for her orders to the police to fire on protesters in the weeks ahead of her ouster. Hasina lives in exile in India. Delhi is unlikely to give in to demands from Dhaka for her extradition.

In an interview to Frontline, Syed Badrul Ahsan, a Bangladeshi commentator based in London, said holding an election without the Awami League would be repeating the mistakes committed by Hasina. Ahsan said banning the party was the disenfranchisement of a sizeable number of voters who still remained committed to the party.

Also Read | BNP and Jamaat’s London huddle stirs political pot in Bangladesh

He even went so far as to predict that if allowed to participate, it would be a tight race between the BNP and the Awami League. A close result would, in fact, be the best outcome for the country, as that would prevent the Jamaat and Islamist parties from gaining ground. But he also acknowledged that at the moment, the Awami League had lost its organisation, with its leaders in exile and those still in Bangladesh afraid to come out due to the upper hand of street mobs.

Ahsan also said with Hasina’s indictment, the best course for her would be to step back from the leadership of the Awami League and enable a new leadership to take charge of the party and rebuild it.

“If Awami League withers away,” Ahsan warned, “the entire history of Bangladesh, which is already under threat, will be wiped out altogether.”

Nirupama Subramanian is an independent journalist who has worked earlier at The Hindu and at The Indian Express.