SPEAKING at the recent annual conference of the Bangladesh Administrative Service Association, Chief Adviser Dr Muhammad Yunus has emphasised the need to create opportunities for young people, asserting that Bangladesh’s large population is not a burden but a valuable resource.

A day later, deputy commissioners proposed the introduction of universal military training for youths, aiming to involve them in the country’s defence efforts.

Of course, this is a political decision, and it requires serious examinations of the proposed programme’s budgetary implications.

We have done some preliminary budget estimates. The good news is that we can introduce the programme progressively over 5-8 years, say beginning with 10 per cent of those turning 18 years as a pilot and then gradually covering the entire cohort of 18-20-year-olds who are able to serve.

The context: seismic demographic shift

IN 50 years since independence, Bangladesh’s population more than doubled from around 70 million (7 crore) to around 174 million (17 crore), turning Bangladesh into one of the most densely populated countries in the world. Despite a rapid fall in fertility, Bangladesh’s population will continue to grow largely due to the momentum effect. The UN Population Division projects that Bangladesh’s total population will reach its peak in 2071 with a population of 226 million.

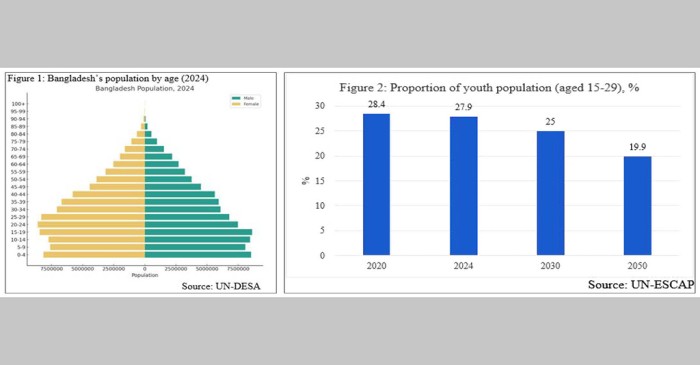

Bangladesh is well into the third phase of demographic transition, having shifted from a high mortality-high fertility regime to a low mortality-low fertility one. As shown in the population pyramid (Figure 1), there is a youth bulge comprising about 28 per cent of the population in the age bracket 15-29.

The UN projects that by 2030, the proportion of youth in the age bracket 15-29 years will decline to around 25 per cent and by 2050 to around 20 per cent. So, this is our demographic moment that comes only once (see Figure 2).

As professor Yunus stressed, the young population is a blessing — a source of strength, energy, and vigour. A country with a large number of young people not only has a large pool of workforce but also a large pool of potential future leaders — often referred to as a ‘demographic dividend’.

However, demographic dividend is not prearranged. It is an opportunity provided by the age structural transition. This window of opportunity opens for a population only once. If missed, it may become a ‘demographic curse’.

A country can “become old before becoming developed,” as we see in the case of Sri Lanka, characterised by a large proportion of elderly population (non-working age) while the nation still struggles with poverty and infrastructure issues. Thus, the country not only has fewer working-age people (i.e., a smaller workforce), but also has to support a large number of people in their older age. Such a demographic situation potentially hinders a country’s economic progress and creates challenges for its social welfare systems.

Thus, an increase in the proportion of young people in a country’s population structure can bring a huge dividend provided this raw power is converted into highly skilled human resources, absorbed in productive employment, and turned into entrepreneurs.

This can be shown by decomposing the neo-classical production function as follows: Y/P = Y/SE x SE/E x E/LF x LF/WP x WP/P, where Y = GDP, P = population, E = employment, SE = skilled employment, LF = labour force, WP = working-age population.

Thus, GDP per capita (Y/P) is the product of: a) productivity gains due to skilled employment (Y/SE), b) proportion of skilled employment (SE/E), c) employment rate (E/LF), d) labour force participation rate (LF/WP) and e) demography, i.e., proportion of working age population (WP/P).

Bangladesh’s demographic dividend may become a mirage. The recent student/youth unrest, which began with a demand for quota reform and ultimately toppled the Hasina regime, is a clear indication of the economy’s inability to absorb these youthful people in productive employment or turn them into entrepreneurs. The official unemployment figure of about 3-4 per cent based on outdated labour force survey methodology does not reflect the reality.

National service: a feasible urgent solution

OUR most critical challenge is preventing the demographic curse and reaping the demographic dividend. Mandatory national service, comprising some basic defence training, IT and general literacy-numeracy, and vocational skills, will not only bring enormous economic benefits but also prepare the country for disaster management, especially due to the climate crisis. It will also act as an effective deterrent against possible threats to our national sovereignty.

Currently, we have around 1.6 crore (15.9 million) youths in the age bracket 20-24, roughly 87 lakh females and 73 lakh males. Of the youth turning 18 years, about 29 lakh are able to serve, excluding child-bearing females (around 25 per cent) and those with various disabilities.

If 10 per cent of the youth turning 18 years are included in the programme in the first year, and Tk 12,000 per month (equivalent to the current minimum wage) is used for each participant, then 5.8 per cent of the total 2024-25 budget proposed by the fallen regime would be required for defence. This is marginally higher than the 5.3 per cent allocated in the proposed 2024-25 budget. This figure rises to 5.9 per cent and 6.2 per cent if training each participant requires Tk15,000 and Tk20,000, respectively.

The above rough and ready estimates assume no change in the existing allocation for other defence expenses. Nor does the exercise consider efficiency gains.

Obviously, budgeting cannot be done in isolation. The first place to find money is reallocation as required by reprioritisation. It should be mentioned here that the fallen regime in its last budget proposed for 2024-25 in June 2024, increased defence budget by 11 per cent over the revised defence budget for 2023–24. Therefore, this has to be examined seriously; the priorities of the ‘new Bangladesh’ cannot be the same as the fallen regimes.

Money can also come from the savings that might result in other sectors, e.g., education, as there will be reduced pressure to expand post-secondary education. If necessary, the costs of such programmes have to be shared through higher taxes for the sake of securing a prosperous future for this country.

Empowering the youth

TRAINING and skill development through mandatory national service is just one element in the supply side of the equation. The pool of available talent needs to be empowered and deployed to yield a demographic dividend. Otherwise, it will be wasted and may even turn into a disruptive force.

Our most critical challenge is preventing the demographic curse. Not only do we have to reap the demographic dividend, but we also have to ensure what is referred to in the literature as the ‘second demographic dividend’. While the ‘first demographic dividend’ due to the rise in the proportion of working-age population is transitory, the ‘second demographic dividend’ can be perpetual.

For this to happen, countries need to invest in skill upgrading, support entrepreneurial initiatives, and create innovative/flexible work environments to allow working even in older age and asset accumulation by workers.

Especially given the advancement in technology, and particularly artificial intelligence, we urgently need to rethink skill development for our youth. Many university degrees may soon become obsolete because the skills they offer are prone to automation.

Ironically, many blue-collar, hands-on jobs are likely to survive because they require mental and motor skills humans have developed over millennia and are really difficult to automate. We consider them low-skill because we take those skills for granted. On the other hand, jobs that require high-level critical thinking will also survive. We need urgent actions to prevent our youth from falling into the ‘middle’.

Act now

PROFESSOR Yunus has rightly understood the key message of youth revolt: the youth should be placed at the heart of strategies, as they are committed to creating a new world that is inclusive, fair, and just. Therefore, it is logical that his government initiates the measures when the aspirations of the revolution are still fresh in the minds.

Anis Chowdhury is an emeritus professor at Western Sydney University in Australia and held senior UN positions in Bangkok and New York in economic & social affairs, and Khalid Saifullah is a statistician with years of experience working in international organisations.