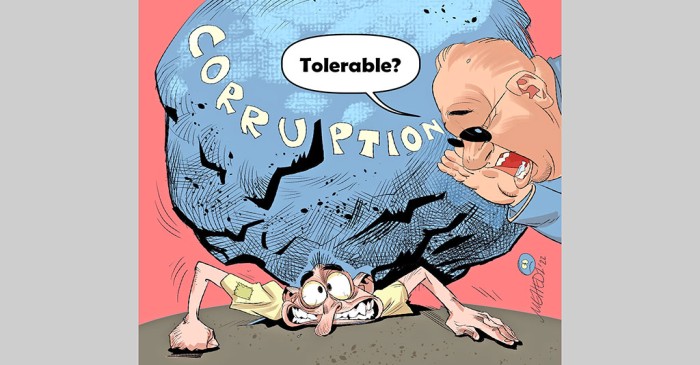

BANGLADESH stands at the crossroads of a national reckoning. Of many serious issues facing the nation, first and foremost is the dire need to combat corruption. According to a Transparency International Bangladesh survey report, citizens of Bangladesh perceive political parties (62 per cent ) and the parliament (40 per cent) as among the most corrupt institutions in the country. In the TIB’s 2023 survey, 72 per cent of the respondents reported paying bribes for routine services to government officials. Pervasive corruption in the police department has always been a serious problem. According to another survey, 82 per cent of the citizens reported the police as the most corrupt public servants. Unfortunately, in the same survey, the country’s judiciary was not far behind, with 75 per cent taking bribes for providing legal services.

Over the last 53 years, the parties in power steadily moved from mischief to corruption and unabated misappropriation of public funds. However, over the last 15 years the country — under the autocratic rule of Sheikh Hasina — was going through a paradigm shift, moving from misrule to mob rule, looting banks and grabbing real estate countrywide, making the term corruption look pale and insipid. For example, in a survey conducted last year by Citizens’ Platform for SDGs, nearly 70 per cent of the youth described corruption and nepotism as the main obstacle to development. Massive transfers of resources from the masses to the elites and from the poor to the riches have significantly increased citizens’ distress about ever-increasing and ballooning unfairness, injustice and inequality. The bubble of anguish, distrust and distress among the citizens — young and old — was expanding and finally exploded on August 5, causing the looters and their leader to flee the country, leaving the economy and public institutions in total collapse.

Politicians are always entrenched in a realm of cravings for self-interest while being brazenly servile to party interest ahead of public interest. If the incumbents are identified as wheelers and dealers, they are expected to be voted out in their re-election bid. However, it is a common experience in most democracies — mostly in developing countries — that under the mostly tampered mechanism of the election process, the voters end up re-electing devious and immoral people to power. Bangladesh is no exception to such corrupt practices.

In electing politicians to the parliament, the voters want qualified candidates who would work in the public interest and fulfil their pledges. If the inducements for becoming an MP are large, it will inveigle many candidates — many with undisclosed information about their past mischief and some with lots of money but inadequate qualification and aptitude (example, businessmen) for the job — who will enter the political process, thus bringing into play the dilemma of adverse selection for the less informed voters.

An interesting insight into the representation of various professionals in the parliament provides an understanding of the nature of our parliament in terms of quality and spread of professionalism in this institution. In 1973, occupational distribution in the parliament was: businessmen (23.7 per cent), lawyers (26.5 per cent), other professionals (30.7 per cent), professional politicians (12.7 per cent), others (7 per cent).

A dramatic shift occurred in 2014 in that businessmen’s representation more than doubled to 54.5 per cent, lawyers and professionals both were cut nearly half to 14.5 per cent and 14.5 per cent respectively, while politicians took 5.4 per cent with unidentified others (10.4 per cent). The 2024 parliamentary composition roughly reflected an overwhelming presence of businessmen, some 70 per cent of the lawmakers with little or no understanding of the complicated provisions of the constitution. The coterie essentially cosseted themselves in voting to enact laws that are machinated to their narrow interests at the cost of the national welfare.

Identifying qualified candidates against the shady ones becomes even more difficult when party nominations are finalised through commodities like auction markets — the highest bidder being nominated. In the process, the entire party machinery gets involved in propaganda and fabrication of credentials about the candidates. The rival party also competes with propaganda blitz. The electors are now trapped in an adverse selection mode by being flooded with misinformation. Here the media, if free from political pressure and future retributions, can play a significant role in minimising adverse selection and the phenomenon of asymmetric information.

After a skewed selection has occurred and a potential corrupt candidate is elected, he/she will have a lot of inducements to engage in mischief — giving rise to the moral hazard issue for the constituent and the society — having little or no control by the voters, especially in developing countries until the next election cycle. For example, here in Bangladesh, it is nearly impossible to bring corruption charges against any politicians of the party in power. This problem is likely to be systematically related to two important parameters of the delegation relationship.

First, the greater the discretionary power politicians are granted, the more reckless they become in misusing their power for personal gain. This is the most importunate feature of the world’s poorest countries, regardless of the promises that may surround new office holders.

Second, the longer incumbents stay in office, the more serious the moral hazard problem may become. That’s because becoming ‘corruptician’ is a bit like losing one’s virginity; there is no going back; the inertia of rent seeking continues unabated. Unfortunately, benign politicians in the system may become corrupt over time, but the corrupt rarely become benign, if ever. This is probably the best argument in favour of term limits for lawmakers, which otherwise may have undesirable consequences for electoral accountability.

Fiscal policy is often linked with corruption, in which the bribing of officials is done by businesspeople for personal aggrandisement, such as dodging taxes and regulations or securing public projects. In a research-based article titled ‘The impact of fiscal policies on corruption: A panel analysis’, Monica Achim, Sorin Borlea, and Andrei Anghelina, using panel data from 185 countries (2005-2014), found that ‘developed countries with high-quality institutions lead to a lower level of corruption, which is in line with expectations. Conversely, in developing countries with low-level institutional quality, corruption increases because of low governance efficiency, under which people may easily circumvent the law.’ The authors’ analysis and findings recommend that governments and policymakers willing to combat corruption need to recognise that the crusade against ‘corruption requires not only the right fiscal policies but also the right way of implementing these policies, recognising the role of quality institutions, which need to prevail in any country’.

The voters of Bangladesh are in a quandary; an adverse selection trap and escaping this trap has become an insuperable challenge. Minimising the occurrences of adverse selection minimises the scope and scale of the corruption and looting as well. To minimise these twin problems, the process of primaries in American democracy, voters in a constituency select their own party candidates through primary ballots for the final election. Prior to the primaries, candidates go through drillings in debates, town hall meetings, and press conferences to explain their policy priorities for the constituencies. Thus, free media and public discourses are the cornerstones of selecting a benign candidate. The media’s influence is so strong in shaping public opinions that elected officials are often recalled for replacements of mischief-mongering elected officials.

For good governance in Bangladesh, there is no alternative to making the Anti-Corruption Commission and TIB as honest, powerful, and responsible institutions as possible. Parliament is the ultimate forum for accountability for all activities of political appointees and public servants. A well-qualified breed of lawmakers with impeccable integrity and an independent Anti-Corruption Commission would be the most effective deterrence against public policy mismanagement and malfeasance, thus guaranteeing delivery of political goods to the citizens.

A constitutional provision barring admission of children of legally proven ‘corrupticians’ into public colleges and universities for higher studies in all areas of learning and expertise would be a great deterrence against corruption and mischief. Their children may also be sanctioned from taking the BCS exam. The chances of corrupt politicians’ children also becoming corrupt are very high because they would be exposed to a corrupt culture and consider that as being normal. Denial of passport to the corruptician and his/her family members may also be added to the provision. These are very ambitious ideas, no doubt.

With the current breed of politicians and those waiting in the pipeline, any hope for corruption-free governance seems to be something of an illusion under the prevailing institutional structure.

Dr Abdullah Dewan, formerly a physicist and nuclear engineer at BAEC, is emeritus professor of economics at the Eastern Michigan University, USA. Humayun Kabir is a former senior official of the United Nations in New York.