The latest findings of Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics pointing out the disheartening ground reality of education and health care in Bangladesh appear to temper the big dreams to become an upper middle-income country by 2031 and a developed one by 2041.

The tremendous successes Bangladesh has gained in both primary health care and education over the decades, albeit the poor allocation of resources, have contributed to a large extent to the reduction of crude poverty and becoming a lower middle-income country in 2015.

But the transforming journey is facing headwinds with many of the gains seeing slowdowns like the increase in child mortality, increase in school drop out rates, the sobering fact of around 40% of the youth neither in education, nor in job or in training. These areas of concern call for significant investment and attention in health and education.

To reach the upper-middle income status, Bangladesh needs to almost double the per-capita income in the next seven years and then another leap would be required to take it to the status of a high-income country with per capita income over $13k. Will that be possible without a drastic change in the economics it follows?

Low skill a major hurdle

A low-skill workforce with low productivity appears to be a major hurdle to achieve the big dream.

Experts have long been urging for special care and higher budgetary allocations in the two sectors of education and health care to transform people into a skilled workforce for the economy.

The success stories across the countries including Singapore and South Korea testify in favour of special investment in education and healthcare and Bangladesh should emulate those models to prepare its labour force.

Take the stories of Bangladesh.

There is a long list of its successes. In 1972, immediately after independence, only one in four could complete primary education, one in five adults could read and write, and one in 20 had access to higher education. The adult literacy rate was 70% and children out of primary schools were less than 21% in 2022. The number of primary schools grew four times in the last 50 years, secondary schools two times and the growth in universities, both public and private, is an astounding number, jumping from 6 to 164.

Bangladesh now runs an education mill of two lakh institutions, 15 lakh teachers for over 4 crore students–more than the total population of Finland, Denmark, Sweden, Norway and Greece.

In the health sector, success is also evident as child and maternal mortality rates have dropped, population growth is in check, life expectancy has risen—though some indicators have reversed, as the latest official data show.

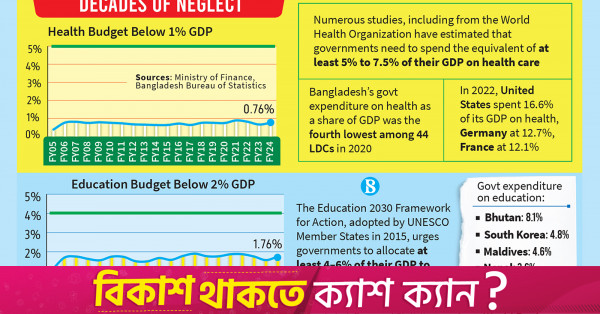

All these positives have been made over the last five decades on modest allocations in education and health, languishing below 2% and 1% of GDP respectively. As a share of annual development outlay, the budget for education and health dropped to 7% and 5% in the current fiscal year from 11.6% and 6.4% of FY15—a period that saw an average 25% of total development budget going to the transport infrastructure sector.

Does it mean Bangladesh needs more roads than education and healthcare? Or is it that Bangladesh has already spent adequately in education and health and there is nothing more to do? In fact, most of the allocations of these sectors went into building constructions and salaries, leaving little for quality. This is evident in recent health and education data and studies.

Education missing focus?

Though thousands of primary schools were nationalised and dozens of public universities established, the secondary education structure followed the model of the one in the British colonial era—one government high school in every district headquarter and several others built with private initiative with the teachers getting basic salary under a government provided monthly pay scheme.

This system fails to attract quality teachers in secondary schools. “93% of secondary students read in these schools. Undoubtedly, the quality and environment of most of these schools are below par,” says educationist Dr Manzoor Ahmed, emeritus professor at Brac University.

From a low-income country, Bangladesh graduated into a lower middle income country in 2015 according to the World Bank standard. It is now on track for graduating from the UN’s least developed country status in 2026.

To achieve four education-related targets of UN sustainable development goals by 2030, Bangladesh has to ensure universal, quality, equitable and inclusive education up to secondary level as well as create opportunity for further education–which are equally crucial for achieving national strategic goals such as reaching middle-income country threshold by 2031 and developed country by 2041.

“It remains a big question whether these goals will really be achieved and how much of the targets of a quality and equitable education for all can be reached despite much progress seen in numbers,” Prof Manzoor writes in his book “Ekush shotoke Bangladesh: Shikkhar Rupantor” (Bangladesh in 21st century: Transformation of education).

Studies also support his doubt about the quality of education.

“Quality is a major concern from primary to higher education. Covid-induced school closure aggravated the situation further,” said Dr SM Zulfiqar Ali, senior research fellow at Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies (BIDS), in a research paper co-authored by Siban Shahana, a research fellow.

He stressed improving incentives and elevating status of teachers as well as addressing their recruitment and training issues for improving overall quality of formal education.

Their study on primary education shows the abysmal level of basic quality in simple Bangla and Math. Nearly 37% of Grade 3 and 30% of Grade 4 students surveyed could not read a given Bangla text, while 56% Grade 3 students could not even identify three given numbers, forget about doing a simple mathematical operation.

The consequence is even acute when it comes to employment—the rate of joblessness among educated youths is higher than the national level. Among the unemployed youths, about 28% hold tertiary degrees, finds a 2022 BIDS study.

“This implies that higher education does not necessarily guarantee a job. Many youths who are looking for a job do not fulfil the demand for skills and capacity,” says BIDS research fellow Dr Badrun Nessa Ahmed, explaining why youths’ employability remains low despite having a university degree and why one in every four graduates remain without a job even after three years of graduation.

She suggested that universities should train students in ICT, improve their English language skills and develop communication and team skills to help graduates find jobs.

The disheartening reality of educated youths in Dhaka, queuing for job recruitment tests at test centres almost every weekend, depicts a harsh picture of the educational sector’s challenges. The doubling of unemployed graduates to eight lakh in just five years further underscores this urgency.

“Most tertiary education academic programmes do not provide students with the opportunities to gain practical exposure to their field of study,” Dr Badrun Nessa said, asking for practical assessments through presentations, teamwork, research and internships in university education.

Data show quality of education

These tell a lot where our education stands and how far it will take the “Smart Bangladesh” vision by 2041. These data answer why not a single Bangladeshi university ranks among the global top 650 in the QS World University Rankings 2024 and why Global Knowledge Index 2023 ranks Bangladesh 112th among 133 countries, at the bottom in South Asia after Pakistan.

When it comes to education spending among South Asian nations, Bangladesh trails only Sri Lanka in allocation.

Does it have anything to do with our limited resources?

Prof Manzoor does not think so. “It can be said that lack of resources is not the reason behind the poor national commitment to education quality. According to Unesco, the share of public expenditure in education in low-income countries is double that of Bangladesh.”

The practice, he finds, is contrary to a middle-income country that Bangladesh hopes to be.

The concern sounds similar to those aired in India and Pakistan as well.

Former chief of India’s central bank Raghuram Rajan thinks India’s biggest challenge is improving education and skills of the workforce.

In an interview with Bloomberg, he said India is unlikely to achieve its goal to become a developed economy by 2047, with so many kids without a high school education and drop-out rates remaining high.

The economist, who is now a professor of finance at the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business, said the country’s growing workforce becomes a dividend when they get “good jobs.” Criticising the Indian government for its focus on high-profile projects, he felt India needs to focus more on sustainable development.

The situation is no better in Pakistan. Quoting a World Bank report, The Dawn newspaper reported last year, low investment in human capital may frustrate Pakistan’s ambition to be an upper middle income country by 2047, a hundred years from its independence.

What lies ahead for Bangladesh, which has already passed the Golden Jubilee of independence?

Though a bit higher than Pakistan, the Human Capital Index value of Bangladesh is lower than the South Asian average and even that of Nepal.

Educationists and economists in Bangladesh have repeatedly stressed that much needs to be done to improve social sectors including health and education as public investment in human capital is much lower than what it should be. Low public investment keeps quality health and education beyond the reach of average people.

Discrimination is very high in education and health sectors, senior economist Prof Rehman Sobhan points out, recommending that the government take necessary steps in the budget to ensure quality in public education and health sectors.

Health successes reversing?

The Human Rights Watch stated, numerous studies, including those from the World Health Organization (WHO), have estimated that providing Universal Health Coverage (UHC) will generally require governments to spend the equivalent of at least 5% to 7.5% of their GDP on health care which is far from our current reality. In the latest election manifesto, the Awami League promised to achieve UHC by 2032, which requires a significant jump in health budget.

The data speaks for itself as the Bangladesh Sample Vital Statistics 2023 report shows that the there are deteriorations in some key health indicators including a fall in life expectancy, a rise in death rates for newborns, children under one year and five years of age, and a drop in contraceptive prevalence rates despite the country once taking pride in these indicators.

Out of pocket health expenditure in Bangladesh is the second highest in South Asia, only after Afghanistan. The Global Health Expenditure database shows Bangladeshi people spend 73% of their health expenditure out of their pockets, which is 19% in Bhutan and 50% in India.

“We need to think of stable and effective policies to implement the National Health Insurance Scheme to minimise the coverage gap and achieve UHC,” says Dr Abdur Razzaque Sarker, a research fellow at BIDS.

Invest in citizens

As Ho Chi Minh, the founding father of Vietnam, aptly stated, “For the sake of ten years’ benefit, we must plant trees. For the sake of a hundred years’ benefit, we must cultivate the people.”

Bangladesh’s founding father Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman had also said, “Investment in education is the best investment.”

Bangladesh is chasing a number of lofty targets like Smart Bangladesh, upper-middle-income country by 2031, developed (high-income) country by 2041, only 17 years from now. The true measure of smartness lies in our commitment to the well-being and education of our people.

It is time for Bangladesh to invest in its greatest asset: Its citizens. The next budget can be a good starter for the journey ahead to reach the targets, or at least get close to them.